Mother Jones recently published a story by Shaun Assael and Peter Keating entitled “The USA Needs a Reckoning. Does Truth and Reconciliation Work?” My mind has raced all weekend with responses. I figured I’d put them down in writing in what I imagine will be the first and only blog post I will ever publish here on this site.

What They Got Right

First, I agree with some of their most basic points:

- Truth and Reconciliation Commissions (TRCs) are not magic.

- TRCs would generally be better described as truth commissions. (Assael and Keating are not the first to point this out. I don’t know anyone who has worked in the field of transitional justice who wouldn’t agree with this point.)

- Uncovering the truth of human rights abuses and oppression doesn’t lead directly to anyone’s definition of “reconciliation” without other work and organizing, which can take decades.

- Finally, I agree that there are people who learn a little about this stuff, claim expertise (as Assael and Keating did explicitly in the podcast on the story), and then figure out how to cash in on it without any accountability to a larger community. Assael and Keating, for example, have now written two feature articles on the Greensboro Massacre and TRC and continue to get basic facts about the events wrong.

Beyond those points, I could fill a book with the problems in the story.

Minimizing Role of Law Enforcement in White Supremacist Violence

In fact, the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission did publish a 500+ page report about the context, causes, sequence, and consequences of the Greensboro Massacre. If Assael and Keating had actually read the report, they would have gotten the timeline of the events that day correct and their account would not have left out the significant role of law enforcement. Instead, they uncritically repeated the Greensboro Police Department’s (GPD’s) defense about being absent from the scene because they were confused about the starting time of the march (even though the march fliers plainly noted the assembly time). They note that the GPD’s paid informant in the Klan phoned that morning to warn his handler that 30-35 Klansmen and Nazi party members leaving a location “awash in weapons” on their way to the parade route. Yet this was hardly the sum total of the information the GPD had. The authors fail to mention that:

- This informant was the driver of the lead vehicle in the caravan, and had been given a map of parade route by the GPD.

- This informant, in the weeks leading up to the march, delivered intelligence regarding the clear intent of the white supremacists to violently confront the marchers and the likelihood that they would be well armed. This informant had even begged the city attorney and his own police handlers to cancel the march as the date approached.

- Winston Salem police had intelligence that they claim was shared with the GPD, that a local Nazi, Milano Caudle, was in possession of a machine gun, was planning on coming to Greensboro “to shoot up the place” (indeed caravan members later testified that Caudle did flash around a machine gun at the house before leaving for the march).

- A police car tailing the Klan and Nazi caravan delivered minute by minute reports as they neared the assembly point, yet no police assigned to parade security were called to the scene as they finished their breakfast at a nearby diner.

One of our central conclusions was that, taken as a whole, these facts illustrate how the police disregarded the evidence available to them in order to underestimate the threat of violence from the Klan and Nazis, and overestimate that from the CWP. Unfortunately, the authors appear to be similarly inclined to disregard and mischaracterize the facts. We made 10 pages of findings of fact with reference to the GPD’s knowledge and actions. The authors chose to select but one—that the GPD did not share with the CWP their information regarding the Klan and Nazi’s plan to confront the march.

Likewise, an entire chapter of the report is devoted to the intelligence collected by the FBI and BATF from undercover agents in the Nazi Party and our major findings were that these agencies failed to share this information with the GPD (not the CWP, as the authors falsely claim), which would have helped to inform their security decisions for the march. We also found that we had no evidence that the federal agent acted to provoke the violence, which did not support the survivor’s claims of federal conspiracy. But the authors took no notice of that fact, as it does not fit their narrative.

Conspiracy is a legal term which carries is a high bar to demonstrate, and we did not have access to adequate evidence to make a finding of conspiracy, especially because the GPD refused to share any information with us due to the city council vote (along racial lines) to oppose the commission’s work. Yet the Assael and Keating—who elsewhere take pains to paint the commission as being in the pocket of the survivors—here do not comment on the fact that our report did not endorse the survivors’ central contention. Instead, they use this finding as evidence of the failure of our work. It just doesn’t follow.

These statements, together with other omissions and mischaracterizations, make plain the authors’ intent to skew the facts to mischaracterize the report and indeed the entire commission as biased in favor of the CWP “to portray them as they wanted to be portrayed.” Yet we have an entire section that also assigns the responsibility for the violence, albeit lesser, to the CWP for their provocative use of language and deliberate goading of the Klan into some sort of confrontation, and the fact that they brought weapons to the march, which, when they returned fire in self-defense, acted to draw fire from the Klan and Nazi shooters.

So our findings did not support the survivors’ main contention of a wide ranging conspiracy on the part of the GPD and federal law enforcement, and found them at least partly responsible for the deaths of their loved ones. Hardly “letting the CWP off the hook.”

Blaming the Victims

Why would “investigative journalists” omit these crucial and well-documented facts? I’d venture it was because that made it easier to paint people who were gunned down by the United Racist Front as irrationally committed to “far-reaching law enforcement conspiracy” theories that they had been “denied protection from the gunmen” and that the killings were “a climax of long-standing racial and class conflicts in the region.” Despite the well-documented evidence in the GTRC report supporting these components of the survivors’ assertions, Assael and Keating imply that the CWP members were responsible for their own deaths because, as the “more moderate forces” in Greensboro complained, “they’d just rag you to death.” I’d expect this kind of argument in the National Review; I used to expect more from Mother Jones.

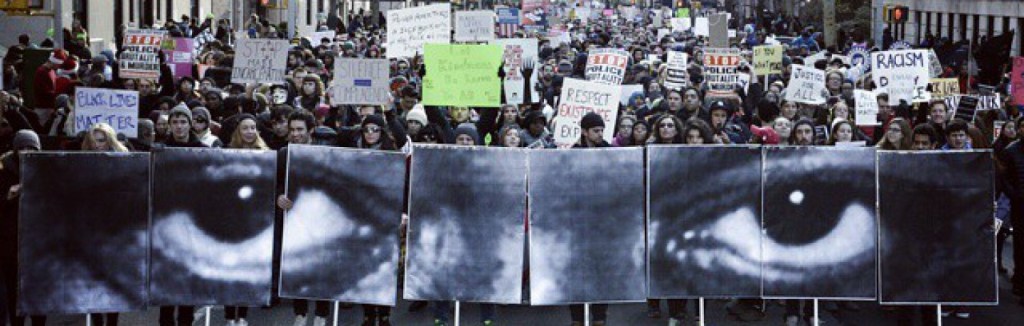

Assael and Keating not only consider themselves experts on truth and reconciliation, they have also staked a place out for themselves as experts on the revival of white supremacist movements in the US. And somehow, after the January 6 assault on the Capitol, they failed to write about the similarities between the Greensboro Massacre and the riots. They failed to write about the ways in which law enforcement regularly overestimates the danger of those organizing for workers rights, Black Lives Matter and related “leftist” causes while simultaneously and tragically underestimating the danger of right wing factions. They failed to explore the connections between white supremacists, law enforcement, and the military in Greensboro in 1979 and the Capitol in 2021. They failed to call attention to the dangers of lies going unchecked and leading to violent outcomes. They failed to mention how a majority of white people in this country are still far too comfortable with people they disagree with being gunned down in broad daylight. Instead, they wrote an article about the Greensboro Massacre that ignores these similarities and instead focuses on blaming “leftists” for harboring conspiracy theories about the murder of their loved ones with the conclusion that TRCs are unsuccessful because they don’t singlehandedly heal long standing societal injustices.

What does success look like anyway?

When Assael and Keating aren’t blaming the victims of the Greensboro Massacre for their own deaths or criticizing survivors’ attempts to address the injustice of racist murderers going free, they are criticizing the Greensboro truth and reconciliation process as an abject failure. They also deem the South African TRC a failure; all it did was “avert mass violence during the transition to majority rule in South Africa.” Big deal.

They criticize the “New York-based non-profit Andrus Family Fund” for not having a working definition of the term “community reconciliation” and yet Assael and Keating never even attempt to define the metrics by which they deem the Greensboro process a failure either. They acknowledge that the Commission clarified many of the facts around the Greensboro Massacre and that we gave voice to many people who had never been heard on the subject before. As far as I can tell, they never bothered to look into whether or not the GTRC’s 29 recommendations were implemented. Had they asked, I could have shared a running tally of how those recommendations have been implemented (see pdf to the right). In the nearly fifteen years since the GTRC released its report, significant movement has happened on the vast majority of the 29 recommendations.

This whole critique reminds me of a call I got from CNN right before the GTRC’s first public hearing. The producer called to ask me if the Klansmen and Nazis who would be testifying were going to be wearing their white supremacist regalia. My response: “I don’t know for sure, but I hope not.” To which the producer responded, “We’d really like a shot of a Klansman in his robes hugging a Communist. Let us know when you’ll have a photo op like that.”

I was dumbfounded. Even when we had CWP members apologizing for their dehumanizing rhetoric leading up to the 1979 events (apologies that Keating and Assael conveniently ignored or never read) and when we had a Nazi shooter, Roland Wayne Wood, apologize to the widows of his victims, I chose not to reach out to CNN for that coverage because forgiveness was NOT an institutional goal of the GTRC. If individual survivors were interested in forgiving the people who killed their loved ones, the process allowed for that. But the GTRC never intentionally encouraged, promoted, or privileged apologies and forgiveness.

In an article I wrote over a decade ago rebutting a piece by James Gibson, one of Assael and Keating’s primary sources for their assessment that truth and reconciliation commissions are ineffective, I talk about the difference in how white people and people of color (specifically Black people) in Greensboro understood reconciliation:

Since the GTRC’s report was released, many Greensboro residents and observers have asked if the process was successful and whether Greensboro is now “reconciled.” Views differ, and the differences follow racial lines. Some residents of Greensboro—usually white—tend to define reconciliation in terms of increased trust in relationships across previous lines of conflict and division. To these residents, the notions of forgiveness (and, less often, apology) tend to be primary in determining the success of the process. Although there were a few notable moments during the truth process in which apologies and

forgiveness were offered, this group tends to assume that Greenboro’s truth and reconciliation process was not successful.Other residents—usually those most negatively and directly affected by the context and events of November 3, 1979—see the first step of reconciliation in terms of institutional reform. Based on its findings about that context and those events, the GTRC made recommendations about reforms in local, county, and state government, including a living wage for city employees and contractors, and establishing a citizens’ review board over the police department. The GTRC made recommendations about the public school system, as well, including incorporating the events and context of November 3, 1979, into the local history curriculum, and about the local media, including a call for more coverage of the context of local conflicts.

For this latter group, the question of whether the truth process in Greensboro was successful remains unanswered. It is clear that, when reporting on the 1979 events and the GTRC process, most local media outlets report the facts more accurately now than they did prior to the report’s release. Similarly, Greensboro residents, as evidenced in part in local blogs, discuss the 1979

events with a more accurate understanding of the facts. Furthermore, although the local government has largely avoided much serious discussion of the GTRC report, community groups have taken up some of the GTRC’s recommendations and are currently working to get them implemented.Reconciliation probably includes elements of both increased trust across lines of difference and reformation of the institutions that have allowed an injustice to occur in the first place. No one in Greensboro would argue that the community is fully reconciled at this point. Some might argue that the city is even more divided than it was prior to the truth and reconciliation process. But the divisions are not new. Greensboro’s truth and reconciliation process and other, more-current events in the city have merely made some residents more aware of the divide, largely along lines of race and class, which existed long before 1979. Time will tell if a better understanding of what led to that division will contribute to a process of healing for Greensboro.

(From “Legitimacy and Effectiveness of a Grassroots Truth and Reconciliation Commission” by Jill Williams, published in 2009 Duke University Law and Contemporary Problems Journal, accessed here.)

In the podcast posted with their story, Assael comes closer to defining reconciliation than he does anywhere in the article. He says that the goal is to “reestablish social norms.” Such a statement is clearly rooted in a worldview that assumes that the status quo is fundamentally just and that the goal in the aftermath of an event like the Greensboro Massacre or the Capitol riots is to get back to the way we were before the violence. Of course someone with that worldview would deem the GTRC’s work to be an abject failure.

The GTRC itself never mentioned apologies or forgiveness in its guiding principles:

Because we recognize that injustice anywhere affects us everywhere, we will seek the truth in all its layers and will seek to provide creative ways for all members of our community to explore their experiences and feelings, engage in fruitful dialogue, and work together in our search for both truth and reconciliation.

Because we enthusiastically embrace the twin principles of honesty and openness, we will work hard to assure that every part of our examination is open, fair, and impartial.

Because we are a totally independent entity, not accountable to or dependent on any particular group or segment of our community, we will earnestly seek to hear and will honestly value everyone’s story. No evidence or testimony will be rejected. In every aspect of our work we will give respect to and provide opportunity for expressions of diverse viewpoints.

We will commit ourselves to the ideal of restorative justice, freed from the need to exact revenge or make recriminations. The work that we do, and the report that we ultimately will issue, will be inspired by the belief that divisions can be bridged, trust restored, and hope rekindled.

In a year that started with a deadly riot at our Capitol based on lies spread about a stolen election, you’d think Mother Jones reporters would put more value on the critical importance of narrowing the range of lies we tell ourselves as a society as a precursor to reconciliation, no matter how reconciliation is defined.

Hard Hitting Investigative Journalists Failed to Track Down the Subject of Their Story

Assael and Keating claim that the GTRC report “casts the communists as they had hoped to be portrayed.” But how do they know how the “communists” wanted to be portrayed by the Commission when they never bothered to interview them for this story? For example, I asked Keating if he’d bothered to try to interview Nelson Johnson. He said that he emailed and called once and, having received no response, decided he didn’t need to press further. Never mind that I had told him in advance that Rev. Johnson doesn’t usually respond to emails and that I’d offered to help him make that connection. The GTRC would have never given up on such a crucial subject after a single email and one phone call. I would have expected better from prize-winning investigative journalists.

The reality is that the survivors were not entirely happy with the GTRC report. For example, some were disappointed that we hadn’t made more findings about the federal government’s role in planning the event. They also weren’t unanimously happy with the finding that they bore some responsibility, albeit lesser, for staging the event in a low-income community and underestimating the potential for violence by the Klansmen and Nazis. (Although some had already apologized for that very thing.) But Assael and Keating just made assumptions about what the survivors wanted without asking them.

They also implied a cozy relationship between the GTRC and the survivors. They claimed that the selection committee for the Commission had “strong ties to Johnson’s Beloved Community Center” but they failed to mention that the Selection Panel for the commission was chaired by the person appointed by Mayor Keith Holliday to that body. They also omitted the fact that seventeen organizations were invited to appoint people to that panel. Those individuals and organizations included the Republican Party of Guilford County, the Greensboro Police Department, the Mayor of Greensboro and plenty of other individuals and bodies who would be surprised to read in Mother Jones magazine that they have “strong ties to Johnson’s Beloved Community Center.” These groups were invited based on a very clear desire by the survivors and their allies in the Local Task Force to design a process that would have legitimacy to the entire Greensboro community and therefore not be connected to or beholden to the survivors alone.

One sentence in here keeps ringing in my ears: “Having already been dealt a sympathetic hand, the Greensboro survivors kept coming back to the table to pursue reconciliation on their terms.” In what world do we call having your loved ones murdered, being blamed for those murders for four decades, losing your jobs, housing, and reputations, and, even in 2021, being the target of a hit piece published in Mother Jones being “dealt a sympathetic hand?”

Personally, I am grateful to the Greensboro Massacre survivors for doggedly continuing to come back to the table to pursue truth and reconciliation in a grown-up sense – not in simplistic terms like apologies and forgiveness – but in terms of institutional accountability and forging networks based on truth and beloved community. It would have been much easier for people like Rev. Nelson and Joyce Johnson to dive headfirst into the so-called truth and reconciliation complex and focus entirely on exporting an admittedly imperfect, but authentic model of grassroots truth-seeking to other communities. Instead, they’ve continued to focus their efforts locally in Greensboro, a place in which their contributions are least appreciated, at least outside of settings like Klan meetings and Mother Jones feature articles. Based on what I know about Mary Harris “Mother” Jones, I think she’d respect them, too.

About the author: Jill Williams was the executive director of the Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission and currently lives in Pulaski, VA, her hometown in the Appalachian Mountains. An accomplished “grifter” in the “Truth and Reconciliation Complex,” she recently was given a raise in her current position leading a local truth-seeking initiative that just barely increased her annual wages from four figures to five.