Austin

The Austin family first made their home in Pulaski, Virginia, where Isaac Austin farmed his own land alongside his wife, Fannie Mae. Together, they raised three daughters: Mary, Mollie, and Nannie. Although little is known about Mary and Nannie, all three were signed onto the Corbin et al. v. County School Board of Pulaski County (1947) lawsuit by their father, Isaac. Their second eldest, Mollie, later settled in the Black agricultural community of Wake Forest, where faith and family shaped her household for generations.

With her husband, Latiney “Carlisle” Farrell, she raised their children — James D. Farrow, Cecil J. Farrow, Shirley A. Sherman, Susie F. Bergsten, Jacqueline Willis, and Gwen F. Houston — while also tending chickens, keeping a garden, and enjoying fresh fruit from the land. The family seldom went into town, relying mostly on what they produced themselves, except for the occasional trip for milk or flour. Mollie also cared for children in the community, working as a babysitter in Wake Forest. Today, her granddaughter Gwen, whom Mollie raised, carries that legacy forward as she pursues her PhD in Education — a powerful reflection of the Austins’ enduring commitment to education and perseverance.

Explore the quilt by clicking on the various elements

For best user experience, use full screen mode

An interactive graphic of the quilt square. The linked information can also be found below.

The overarching theme of this quilt square is the Austin family’s connection to the countryside. In the lower half of the quilt, the foreground of a farm is illustrated with fabrics in shades of greyish gold, purple, and pink, showcasing the rolling hills of Southwest Virginia. Red and purple pentagons are layered to symbolize a barn. The upper half of the quilt depicts a sunset-colored sky, using light gold fabrics to represent the atmosphere.

Learn More About the Austin Family

Artifacts By Family Member

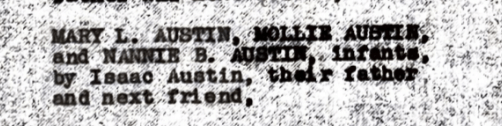

This document ensures that all family members—Mollie, Mary, Nannie, and Isaac Austin—are represented by name on the quilt.

Isaac Austin is the father of the Austin family.

Mary Austin is the eldest daughter signed onto the case

Mollie Austin is the second-oldest daughter signed onto the case

Nannie Austin is the youngest daughter signed onto the case

Mollie Farrow (neé Austin)

Symbolic Representations

Church

Mollie Austin was a devoted member of the Wake Forest New Pentecostal United Holy Church at 200 Wake Forest Rd, Blacksburg, VA. The Wake Forest New Pentecostal United Holy Church was a historic church for the area’s community. However, the congregation has declined over the generations due to the aging population of churchgoers, resulting in its recent closure.

Newspaper Clipping

Old folks in Wake content

Continued From Page 27

Mollie Farrow, who’s lived in Wake Forest 20 years, still misses Pulaski. She left her friends there to follow her husband to Wake Forest. But she likes living in the country, and finds the country store at McCoy and the shops in Blacksburg are close enough to take care of her shopping needs.

George W. Page, a Wake Forest resident for 53 years, can often be found out on a crisp day surrounded by eager hounds ready to help with a hunt. He’s killed two turkeys and two deer in the recent past.

“This is my home,” Page says simply about Wake Forest’s attractions.

Page waved and called greetings to several white men driving truckloads of wood cut from the forests. The whites in McCoy and other nearby communities aren’t strangers to Wake Forest residents. Some of their fathers worked together in the mines. Today their children work together at the Radford Arsenal, and pass the time of day at the McCoy store.

Wake Forest has been integrated occasionally, Eaves reported. “We have had some whites in here,” she said, “and they’ve been real nice and never gave us any trouble.”

The real old-timers in Wake Forest are the Pages. Regina Page, 76, lives there with her 81-year-old husband. They lived all over—in Hampton, Washington, D.C., Detroit—before coming back to Wake Forest.1

“I guess I’ll live here until I go to the bone yard,” Page said amiably…

Welcome to Wake Forest Sign

Mollie Farrow’s news article discusses how she enjoyed her move to Wake Forest and the country life that came with it.

Wake Forest is a historically African American town with deep roots in the descendants of enslaved and formerly enslaved people from the Kent Plantation. According to oral history, James Kent permitted newly freed enslaved persons to settle in the Wake Forest area on his land. During Reconstruction through the 1920s, farming and railroad-related industries were Wake Forest residents’ primary employment sources.2

Pulaski County Sign

The sign is meant to show that Mollie Farrow missed Pulaski but truly loved Wake Forest, highlighting the contrast between the two places as referenced in the article. Pulaski was initially known as “Mountain View Plantation” and was owned by a man named Robert Martin Jr. With the construction of the Virginia & Tennessee Railroad in 1854, the area became a railroad stop named “Martin’s Tank.” The land was primarily used for agriculture during the Civil War and Reconstruction eras. The discovery of coal deposits in 1877 spurred the area’s shift to industrial land use. Pulaski received its modern name after the Martin family sold their land to various companies, including the Pulaski Land and Improvement Company.3

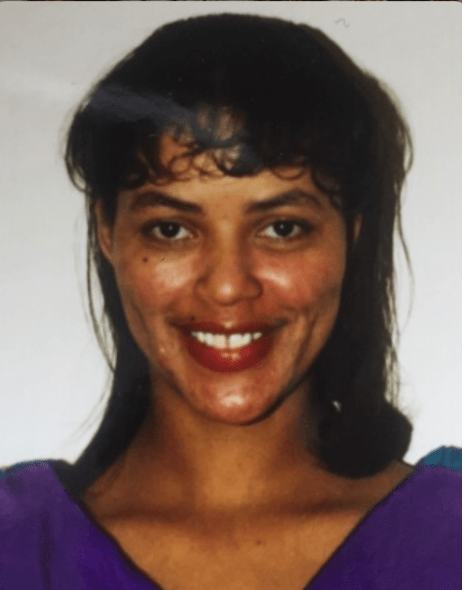

Donna Farrow Austin

The image of the woman is Donna Farrow Austin, Mollie Austin’s daughter; she is used to bring a face to the family, so the quilt is more relatable.

Isaac Austin

Symbolic Representation

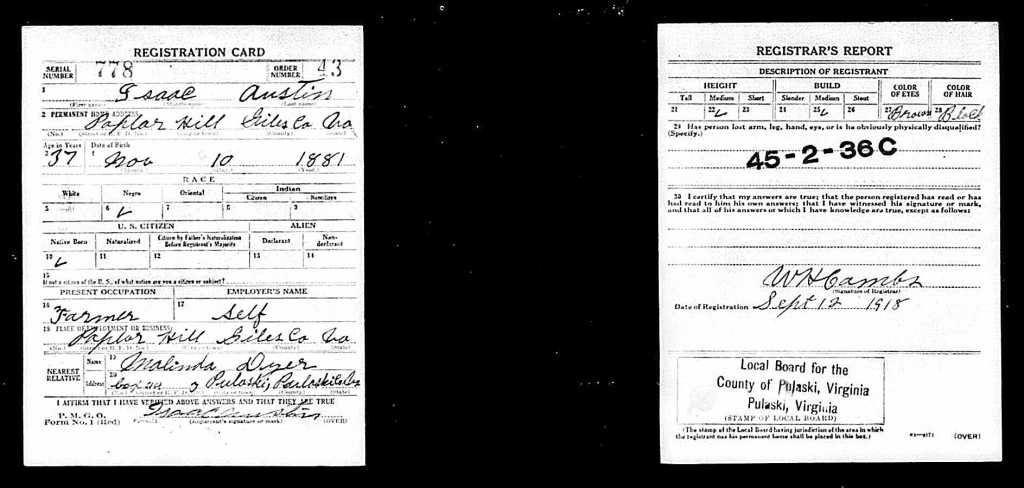

Issac Austin World War I Draft Registration Card

We included Isaac Austin’s registration card because it highlighted his work as a self-employed farmer. Draft Registration Cards provided critical information and insights about several families and family members involved in the Corbin et al. v. County School Board of Pulaski County, VA. et al. case.

Garden Tools

Used to show how the Austin family, specifically Isaac Austin, worked and lived through a rural farming lifestyle. Our nation’s history reflects the many barriers to land ownership and financial independence for Black farmers due to widespread racial discrimination. Generational debt was perpetuated by sharecropping and discriminatory New Deal policies, making it harder for Black farmers to thrive. However, Black farmers began to use their ingenuity and resilience to form cooperatives and support their community. By 1954, 129,854 non-white farmers in the South wholly owned and operated their farms.4

Corn

Isaac Austin worked as a self-employed farm laborer. While none of the collected documents referred to the type of crop he raised, we included a symbol of farming to represent Isaac Autin’s work and the family farm.5

Mary Austin

Mary Austin was a houseworker, and we represented her occupation through tools she may have used during that time. In the 1950s, it was difficult for African American women to acquire skilled labor jobs. During World War II, Black women were encouraged to help the war effort by taking domestic labor jobs so that white women could work in the manufacturing industry. In 1960, around 33 percent of Black women worked as domestic laborers. Also, in the 1960s, less than 20 percent of Black women held clerical jobs, compared to around 50 percent of white women.

- “Southwest Virginia – Genedge.” Genedge. July 19, 2024. https://genedge.org/who-we-are/regions/about-southwest-virginia/. ↩︎

- “Historic Wake Forest, Virginia.” Gathering Blacksburg History. March 15, 2025. https://gatheringBlacksburghistory.org/historic-wake-forest-virginia. ↩︎

- “History: Town of Pulaski.” http://www.pulaskitown.org/history/. ↩︎

- USDA. “Black Farmers in America, 1865-2000: The Pursuit of Independent Farming and the Role of Cooperatives.” October 2002. ↩︎

- “Pulaski County: Land Use.” https://www.pulaskicounty.org/compplan/assets/documents/draft/land-use.pdf. ↩︎