Corbin

The Corbin family made their home in Pulaski, Virginia, where Dr. Percy Casino Corbin trained at Shaw University to become the county’s first Black physician and a steadfast advocate for educational equality. After moving through Roanoke and Salem, he chose Pulaski because no Black doctor served the region for miles. Known for speaking plainly in PTA and NAACP meetings, he pushed for safer, fairer schooling, standing alongside educator Chauncey Depew Harmon, even when their honesty drew criticism and professional consequences. He remained active in the NAACP for decades, contributing faithfully and maintaining relationships with civil rights leaders like attorney Oliver Hill. In 1947, Dr. Corbin and his son Mahatma were among the plaintiffs in the Corbin et al. v. County School Board of Pulaski County (1947) lawsuit. At home, he taught his children that you stand up because it is right—not for recognition—and that before judging someone else, “you look in the mirror yourself.” The Corbin quilt square reflects this legacy of courage, service, and unwavering commitment to community.

Explore the quilt by clicking on the various elements

For best user experience, use full screen mode

An interactive graphic of the quilt square. The linked information can also be found below.

This quilt square features a geometric assemblage of a wide variety of fabrics. The pictures and documents are sliced into the shape of the fabric they are overlaid on. The block is simplistic in nature, but overall, it represents the Corbin family’s commitment to human service and Dr. Corbin’s trailblazing strides in Pulaski County. The quilt also reflects Dr. Corbin’s connections to the medical profession, with his children eventually following in his footsteps in human service and helping professions.

Learn More About the Corbin Family

Artifacts by Family Member

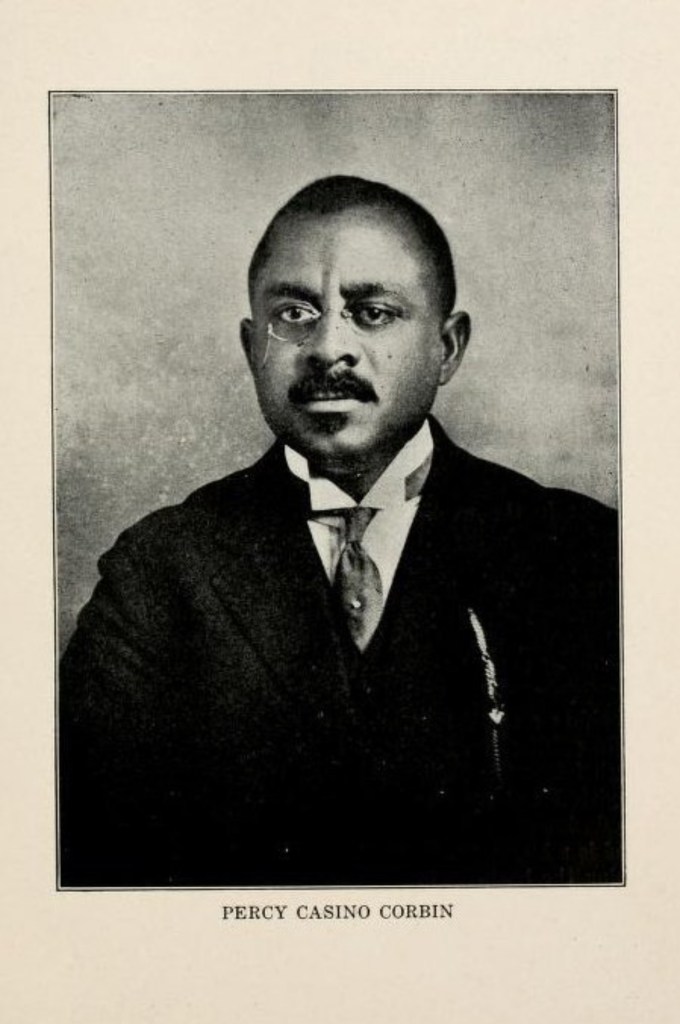

Dr. Percy Casino Corbin

Summary

Born on June 2, 1888 in Athens, Texas, Dr. Percy Corbin initially attended medical school at Howard University in Washington, D.C.,1 which began instructing aspiring Black physicians in the late 1860s.2 Dr. Corbin transferred to Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, where he received his M.D. from Leonard School of Medicine in 1911. The Leonard School of Medicine was established in 1880 to fill the gap in institutions in that region of the country, educating Black physicians until 1919.3 Dr. Corbin relocated to Pulaski to fill the need for physicians in the rural community.4 There Dr. Corbin and his wife Evelyn started a family of five kids, Jacqueline, Percy Jr., John Alphonso, Maurice, and Mahatma.5

Symbolic Representation

Photo of Dr. Percy Casino Corbin

Doctor Percy Corbin served as the President of the Pulaski chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). His involvement in the NAACP allowed him access to other community leaders, such as Dr. Chauncey Depew Harmon, and in 1938, an opportunity presented itself to improve the Calfee Training School. 6 A fire burned the original school building in 1938, and it needed to be rebuilt. Dr. Corbin and Dr. Harmon pleaded with the community via the Southwest Times to pull together support to educate the Black students while they were rebuilding. The school was rebuilt, but the school board decided that it would only educate elementary school students and that secondary students would bus to Montgomery County to attend Christiansburg Institute.7

In 1947, Dr. Corbin pursued legal counsel from the NAACP, Oliver Hill, Spotswood Robinson, and Martin A. Martin. This network of individuals filed a lawsuit against the Pulaski County School Board. This lawsuit involved Dr. Corbin, his son Mahatma, 23 other parents, and their 54 children to argue that the school board had violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, citing the following complaints8:

“(1) That defendants discriminate against them on account of their race, in failing to provide facilities for the elementary education of Negro children equal to facilities afforded white children;

(2) That defendants discriminate against them on account of their race, in failing to provide transportation to and from school for Negro children equal to such transportation furnished white children;

(3) That defendants discriminate against them on account of their race, in failing to enforce the Compulsory School Attendance Law of the State of Virginia as to Negro children as this law is enforced as to white children; and

(4) That defendants discriminate against them on account of their race, in failing to provide secondary or high school facilities for Negroes equal to the high school facilities provided for white children.”9

The judge found no evidence of discrimination against the plaintiffs because Pulaski High School, the white school, was comparably inadequate despite the photo evidence from the plaintiffs.10 The judge did not hold the county accountable for its failure to provide a Black high school in the county that would alleviate the plaintiff’s complaints. However, an appellate judge overturned the initial ruling.11 Secondary students from Pulaski and surrounding counties continued to attend Christiansburg Institute until it closed in 1966, and Pulaski County schools fully desegregated in 1967.12 Ultimately, Corbin’s lawsuit shifted the NAACP’s strategy, the National Archives writing that they “rolled out a new strategy attacking segregation head-on in the Supreme Court.”13

Medicine Bottle

In 1918, the influenza pandemic started spreading in the United States, likely originating from soldiers returning from Europe during World War I. The virus infected approximately 25 percent of the US population, and roughly 670,000 people died. By the summer of 1918, the deadly virus began infecting Virginia’s residents, lasting for 13 months. In Virginia, over 300,000 people caught the virus, with 15,679 reported deaths. Rural communities like Pulaski suffered greatly during the pandemic.14 Doctor Percy Corbin played a crucial role, being the only Black physician in Pulaski, caring for both Black and white residents to slow the spread.15 Supposedly, Dr. Corbin was said to have invented a cure for the flu; “he never lost a patient,” said his daughter Jacqueline.16

White Coat

In 1913, Dr. Corbin moved his medical office to the rural community of Pulaski, Virginia. Dr. Corbin was the only African American doctor in the area during this time. At first, Dr. Corbin primarily served African Americans in Pulaski, but as word spread about his medical practice, he began to serve white patients as well as Black patients.17

Horse

During the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, Corbin’s medical expertise and care for his community were evident as he traveled by horseback to care for patients as the influenza pandemic spread throughout Pulaski. Dr. Corbin and four other doctors in the area worked tirelessly for several weeks to stop the spread of the disease. Ultimately, ninety-two Pulaskians died during the 1918 Influenza Pandemic, but the outbreak could have been significantly worse on townspeople if not for the efforts of Dr. Corbin.18

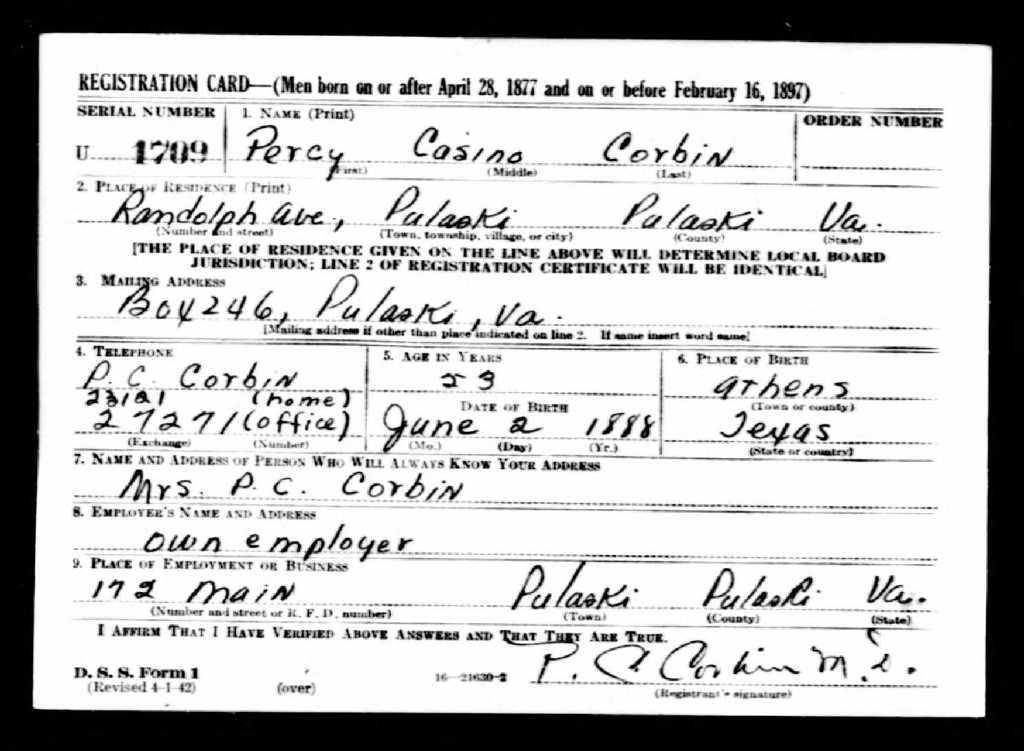

World War II Draft Registration Card

As listed on his World War II Draft Card, Dr. Corbin was self-employed, seeing patients in his home and around town. The Corbin home was located on Randolph Avenue, downtown.19 This was a particularly controversial living arrangement for a Black family in the early 1900s. Jacqueline Corbin Pleasants, daughter of Dr. Corbin, alluded to this in her 1995 oral history interview: “I hate to say that, but some of our own folks didn’t like us because we lived downtown.” The family had paved streets, running water, and electricity, causing other Black Pulaski residents to have “attitudes,” said Pleasants.20 Also listed on the draft card is Dr. Corbin’s age; he was fifty-three years old at the time. During World War II, the Selective Service System conducted the fourth draft registration, which included men born on or after April 28, 1877, or before February 16, 1897. This was known as the “Old Man’s Draft. ” These men were not subjected to service, but the government wanted to catalog their information. 21

Mahatma Corbin

Summary

Mahatma Navarro Corbin was born on November 18, 1931, to parents Dr. Percy and Evelyn Corbin.22 He was the youngest of five children, and according to his older sister Jacqueline, their father named him Mahatma because “daddy admired Mahatma Gandhi…[and] what he was doing in his country for his people.”23 In 1957, after his time in the Air Force, Mahatma married Lucille Agee and they had three children: Christi, Alexander, and Shelley.24

Symbolic Representation

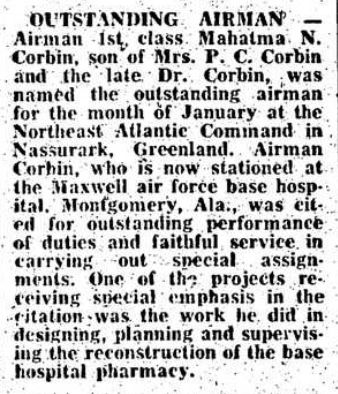

1953 Photo of Mahatma Corbin

While Mahatma was attending high school, his father launched the trailblazing 1947 Corbin et al. v. County School Board of Pulaski County, VA. et al. lawsuit. Later in life, Mahatma enlisted in the Air Force and served four years as a Basic Airman in Greenland. During the Cold War, the United States constructed an Air Force base in Greenland.25 The construction of this facility is known as “Operation Blue Jay,” and its purpose was to house “long-range bombers closer to the Soviet Union and China.”26 Throughout his life, Mahatma worked several jobs, according to his children, “he couldn’t bear to just sit at home,” as working was his hobby. After the military, he worked as a journeyman pipefitter. After he retired, he returned to work at White Castle and Home Depot, where he found joy in customer interactions and staying busy. Overall, Mahatma Corbin lived a long life filled with joy, love, and generosity.27

Tip Jar

In his later years, Mahatma Corbin gained the reputation of being a good tipper. Mahatma, a generous and cheerful tipper, left hearty gratuities, brightening servers’ days with kindness and appreciation.29

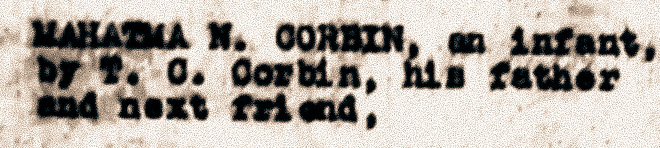

Named Participant List

While Mahatma was attending high school, his father launched the Corbin et al. v. County School Board of Pulaski County, VA. et al. lawsuit on his behalf. Traveling several miles from Pulaski to attend Christiansburg Institute in Montgomery County, deprived Mahatma of the ability to participate in extracurriculars.30 In an oral history interview, his sister Jacqueline testified to this, saying that CI students traveled “on broken down buses that had been discarded for the other students, and they would have to leave home in the dark. And they would get back at dark.”31 The lawsuit aimed to reveal how this arrangement violated the Fourteenth Amendment by failing to provide equal protection for students like Mahatma. The image of the named participant list reads, “Mahatma N. Corbin, and infant by P.C. Corbin, his father and next friend.”

Jacqueline Corbin Pleasants

Summary

Jacqueline Corbin Pleasants was born on January 8, 1916, the eldest daughter of Dr. Percy and Evelyn Linscome Corbin. Jacqueline attended Calfee Training School at the original building before the 1938 fire and graduated in 1932. 32 Jacqueline attended Bluefield State University in West Virginia after graduation for two years. Bluefield State University, originally Bluefield Colored Institute, was founded in 1895 as a post-secondary school to serve “the children of Black coal miners.”33

Symbolic Representation

Certificate of Marriage

In 1940, Jacqueline married Dr. A.W. Pleasants in Pulaski on June 10.34 The couple settled in Lexington, Virginia, where they had three children: Althea Hitola Henderson, J. Carmen Pearson, and A.W. Pleasants III. After she died in 2013, Jacqueline Virginia’s Senate and House of Delegates recognized Jacqueline, enacting a joint resolution to honor and celebrate her memory. This resolution listed her many contributions to the community of Lexington which include, but are not limited to, the “League of Women Voters, the local mental health association, Carilion Stonewall Jackson Hospital Women’s Auxiliary, the Lylburn Downing School band boosters, the Six O’Clock Club, Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority,” and the treasury of the local Democratic Party.35

Other Artifacts

Helping Hands

Following their father’s footsteps, the Corbin children entered into human service and helping professions. Jacqueline Corbin Pleasants was deeply involved in her local community in Lexington, Virginia, working with Girl Scouts, the League of Women Voters, the local mental health association, and Carilion Stonewall Jackson Hospital Women’s Auxiliary.36 Maurice Corbin worked in the US Army Medical Corps owned two private medical practices in the D.C. Metro area, was a professor of psychiatry at Howard University, and served on the Saint Elizabeth’s Hospital and the D.C. Government’s Commission of Mental Health staff.37 Percy Corbin Jr. enlisted in the Army on February 17, 1941, during World War II.38 Mahatma Corbin worked diligently even after retirement from the Air Force, spreading joy in his everyday work interactions.39 Overall, the contributions of Dr. Corbin and Ms. Evelyn Corbin’s children exemplify a deep dedication to service.

Sources

- Tripp, N. Wayne, and Dictionary of Virginia Biography. “Percy C. Corbin (1888–1952)” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities, December 7, 2020, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/corbin-percy-c-1888-1952. ↩︎

- Lloyd, Sterling M. 2006. “History.” Howard University College of Medicine. https://medicine.howard.edu/about/history. ↩︎

- Murray, Elizabeth. 2006. “Leonard Medical School.” NCpedia. https://www.ncpedia.org/leonard-medical-school. ↩︎

- “Percy Casino Corbin,” Virginia Changemakers, accessed April 2, 2025. https://edu.lva.virginia.gov/changemakers/items/show/33. ↩︎

- “Dr. P.C. Corbin Negro Physician Dies in Detroit,” The Southwest Times, July 7, 1952, page 1. ↩︎

- Tripp, N. Wayne, and Dictionary of Virginia Biography. “Percy C. Corbin (1888–1952).” ↩︎

- Dean, Amanda, “‘We don’t want them in our schools”: Black School Equality, Desegregation, and Massive Resistance in Southwest Virginia, 1920s-1960s’” Master’s Thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 2023, http://hdl.handle.net/10919/115163. (31-34). ↩︎

- Tripp, N., and Dictionary of Virginia Biography. “Percy C. Corbin (1888–1952).” ↩︎

- Corbin et al. v. County School Board of Pulaski County, VA. et al. 84 F. Supp. 253 (W.D. Va. 1949) May 2, 1949. ↩︎

- Corbin et al. v. County School Board of Pulaski County, VA. et al. ↩︎

- Dean, Amanda, “‘We don’t want them in our schools.” (59-61). ↩︎

- Desegregation of Virginia Education (DOVE) Research Resources Guide, Pulaski County School Board Minutes, December 16, 2019, https://dove.gmu.edu/index.php/blog/. ↩︎

- National Archives and Records Administration. 2006. “Part IV: Records in the Office of Regional Archives Service, NARA–Mid-Atlantic Region.” In Federal Records Relating to Civil Rights in the PostWorld War II Era, compiled by Walter B. Hill Jr. and Lisha B. Penn, 227-236. Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration. https://www.archives.gov/files/publications/ref-info-papers/rip113.pdf. ↩︎

- Caelleigh, Addeane. “Influenza Pandemic in Virginia, The (1918–1919)” Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities, December 7, 2020, https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/influenza-pandemic-in-virginia-the-1918-1919. ↩︎

- Tripp, N., and Dictionary of Virginia Biography. “Percy C. Corbin (1888–1952).” ↩︎

- Pleasants, Jacqueline. “Interview with Jacqueline Corbin Pleasants.” Conducted by Dr. Wayne Tripp, May 12, 1995, Wayne Tripp Collection, Calfee Center. October 25, 2023. ↩︎

- Tripp, N., and Dictionary of Virginia Biography. “Percy C. Corbin (1888–1952).” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- National Archives At St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri, Records of the Selective Service System, World War II: Fourth Registration, “Percy Casino Corbin,”147, 1942. ↩︎

- Pleasants Jacqueline, “Interview with Jacqueline Corbin Pleasants.” May 12, 1995. ↩︎

- National Archives At St. Louis. “Selective Service Records.” National Archives. Accessed April 2, 2025. https://www.archives.gov/st-louis/selective-service. ↩︎

- Butler Funeral Home, “Official Obituary of Mahatma Corbin,” April 20, 2021, https://www.butlerfuneralhome.net/obituary/Mahatma-Corbin#obituary. ↩︎

- Pleasants Jacqueline, “Interview with Jacqueline Corbin Pleasants.” ↩︎

- Butler Funeral Home, “Official Obituary of Mahatma Corbin.” ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Army University Films, “The Big Picture: Operation Blue Jay,” Army University Press, accessed April 2, 2025. https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Films/The-Big-Picture/big-picture-227/#:~:text=Thule%20(pronounced%20too%2Dlee),U.S.%20Space%20Force%20in%202019. ↩︎

- Butler Funeral Home, “Official Obituary of Mahatma Corbin.” ↩︎

- “Outstanding Airman” The Southwest Times, May 10, 1953, page 6. ↩︎

- Butler Funeral Home, “Official Obituary of Mahatma Corbin.” ↩︎

- “Percy Casino Corbin,” Virginia Changemakers, accessed April 2, 2025. https://edu.lva.virginia.gov/changemakers/items/show/33. ↩︎

- Pleasants Jacqueline, “Interview with Jacqueline Corbin Pleasants.” May 12, 1995. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- National Park Service. “President’s House, Bluefield State University.” https://www.nps.gov/places/president-s-house-bluefield-state-university.htm. ↩︎

- Commonwealth of Virginia Certificate of Marriage for Dr. Alfred Wm. Pleasants Jr. and Jacqueline Corbin, 10 June 1940, file no. 28984, Pulaski, Virginia. ↩︎

- SJ50: Celebrating the life of Jacqueline Corbin Pleasants, Virginia State Senate and House of Delegates, (2014). ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- “Maurice Corbin Obituary,” The Washington Post, 2012. https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/washingtonpost/name/maurice-corbin-obituary?id=5996167. ↩︎

- US National Archives & Records Administration, Percy C. Corbin, Electronic Army Serial Number Merged File, ca. 1938 – 1946, World War II Enlistment Records-Record Group 64, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD, accessed April 2, 2025. ↩︎

- Butler Funeral Home, “Official Obituary of Mahatma Corbin.” ↩︎