Dyer

During the early to mid-1900s, John Henry Dyer and Malinda Austin Dyer raised their children along Robinson Tract Road. Their son, John Schaffer Dyer, was listed in the Corbin et al. v. County School Board of Pulaski County (1947) lawsuit, signed by his father on his behalf. Though John’s life was tragically cut short, his legacy lived on through a community award created in his honor.

The Dyers were known for breaking barriers — from Moses Dyer’s military service to Amos Dyer’s later contributions to NASA’s STS-1 space shuttle launch in 1981 — and for their dedication to civil rights, faith, and family. Generations later, their descendants continue to carry forward that same spirit of strength and perseverance, remaining deeply connected to the land and community their family once called home.

Explore the quilt by clicking on the various elements

For best user experience, use full screen mode

An interactive graphic of the quilt square. The linked information can also be found below.

The different fabrics are arranged to represent the breaking of barriers, like boulders, with specific milestones and stories at the edge of these rupturing barriers. The quilt square features predominantly purple fabrics to symbolize the family’s togetherness.

Learn More About the Dyer Family

Artifacts by Family Member

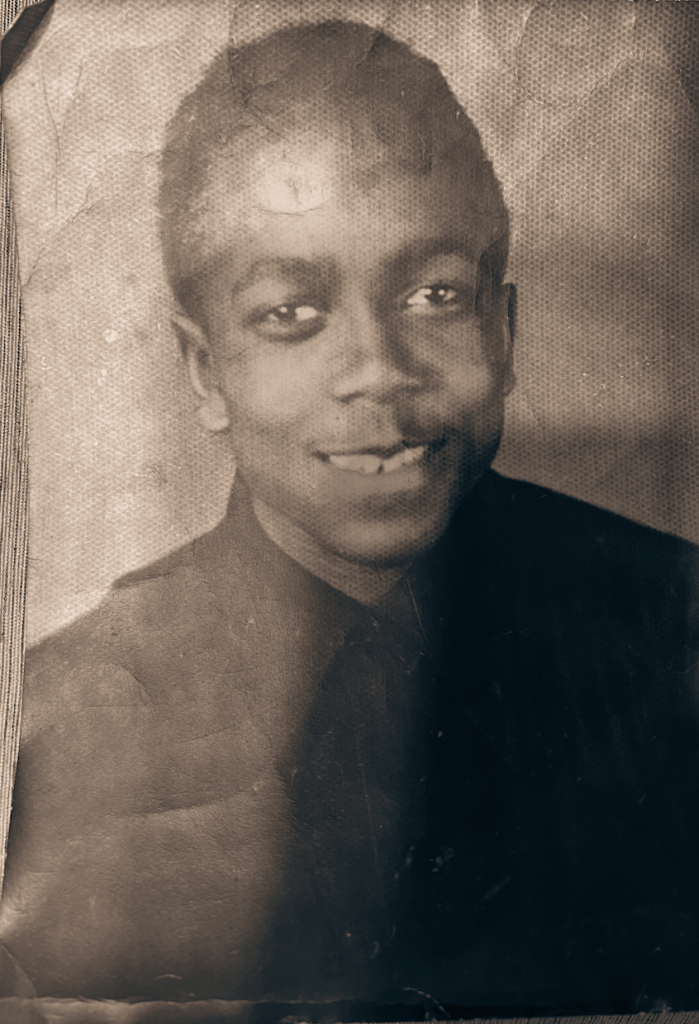

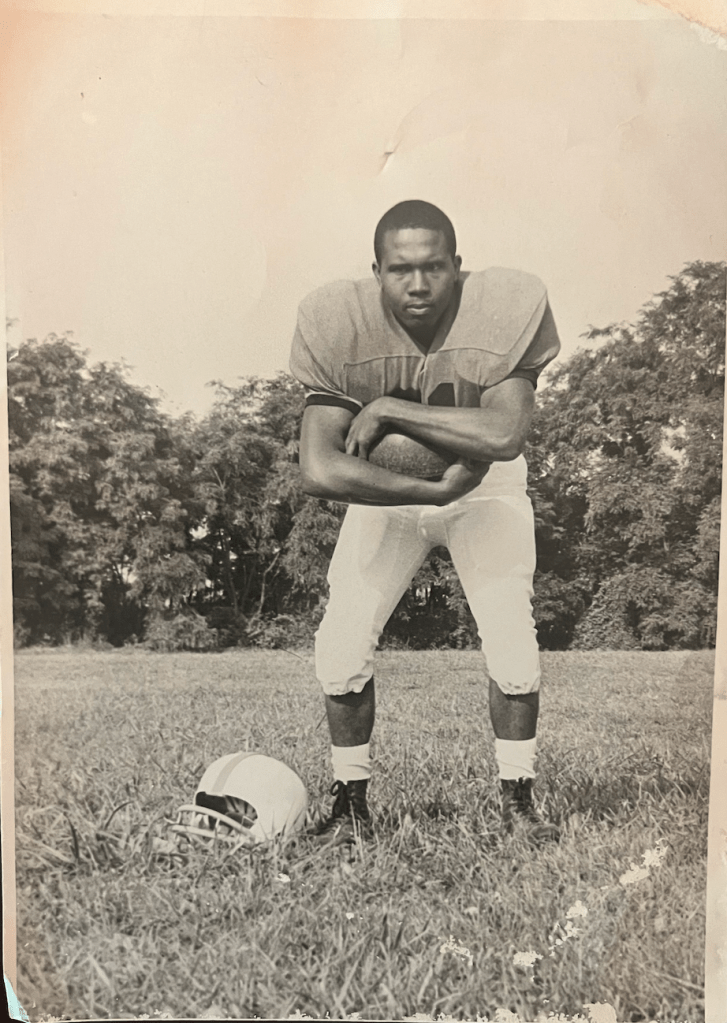

John Schaffer Dyer

Summary

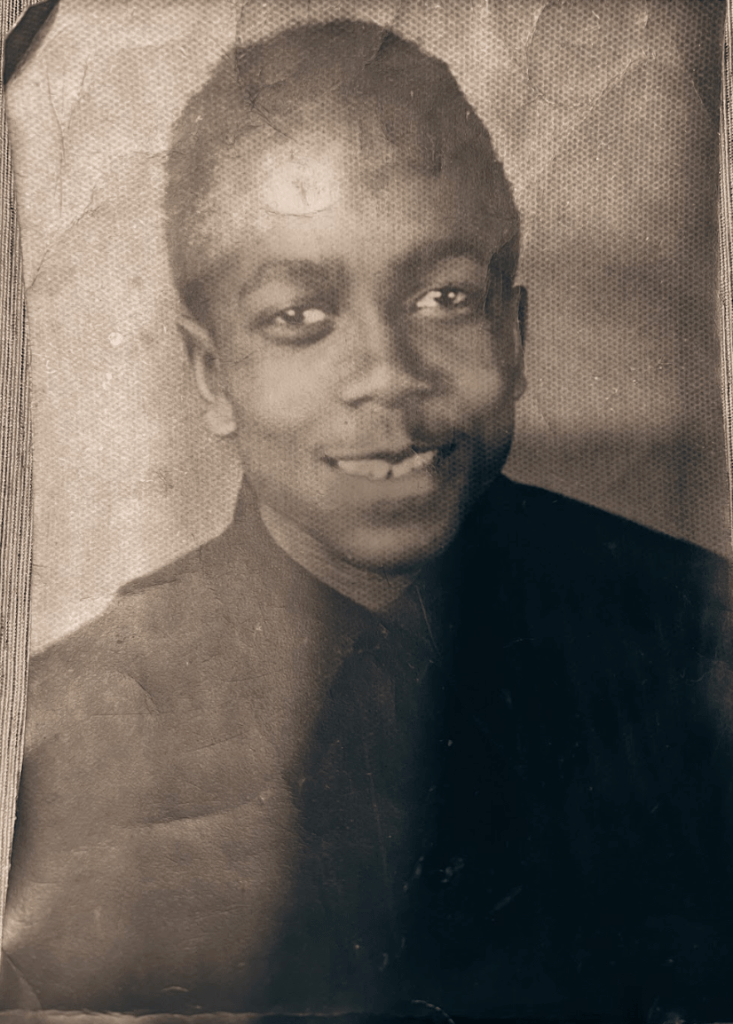

John Schaffer Dyer was born May 21, 1931, to parents John Henry Dyer and Malinda Austin Dyer.1 John attended Christiansburg Industrial Institute. John is the only Dyer child cited in the 1949 lawsuit, alongside his father, Henry. Tragically, at just seventeen, John suddenly passed away in a car accident.2

Symbolic Representation

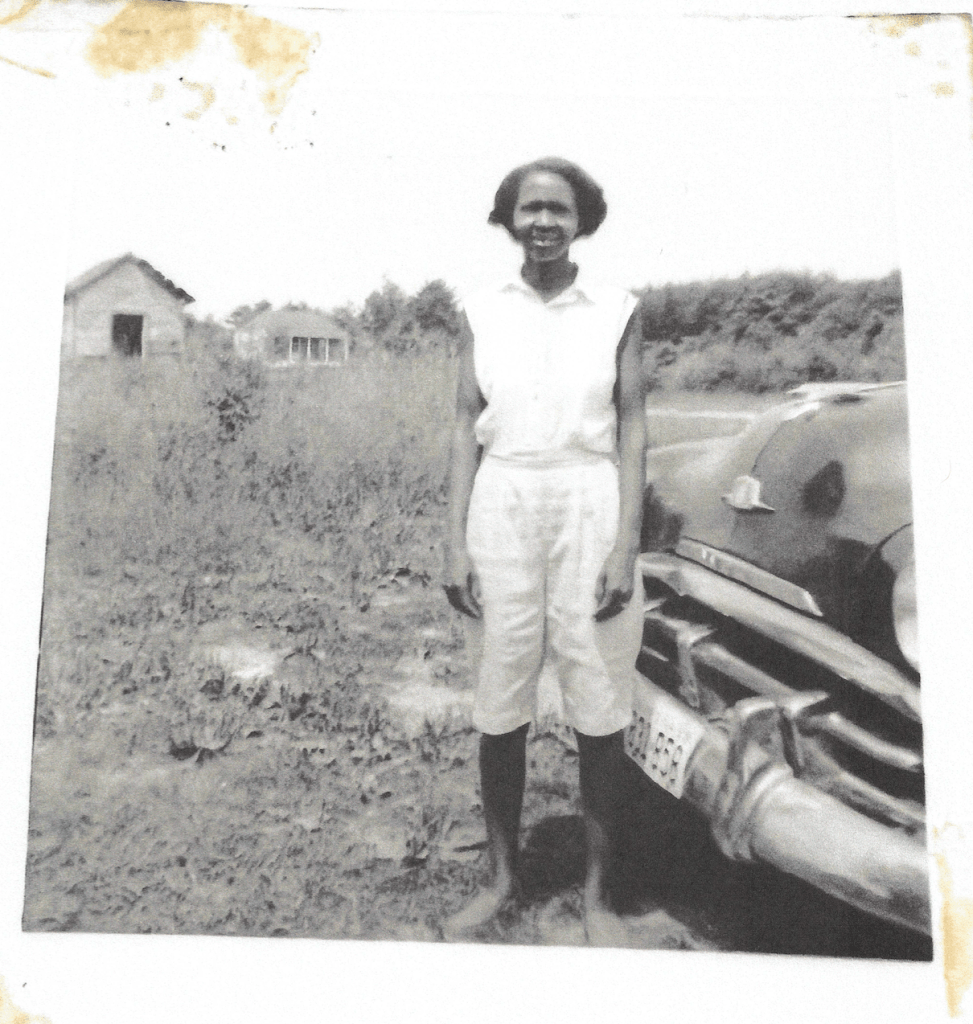

Photo of John S. Dyer

In 1951, Christiansburg Institute created a trophy, the “John S Dyer Award,” in memory of the student, awarding it to Edward S Perry. Without John’s and his parents’ bravery, the family would not have established a precedent for breaking barriers in the future. 3

Named Participant List

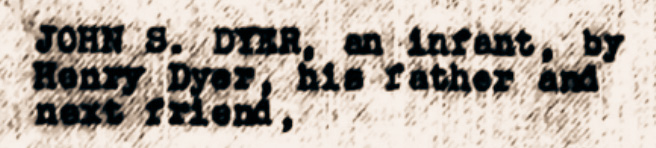

The named plaintiff list from the 1947 lawsuit reads “John S. Dyer, and infant, by Henry Dyer his father and next friend.”4

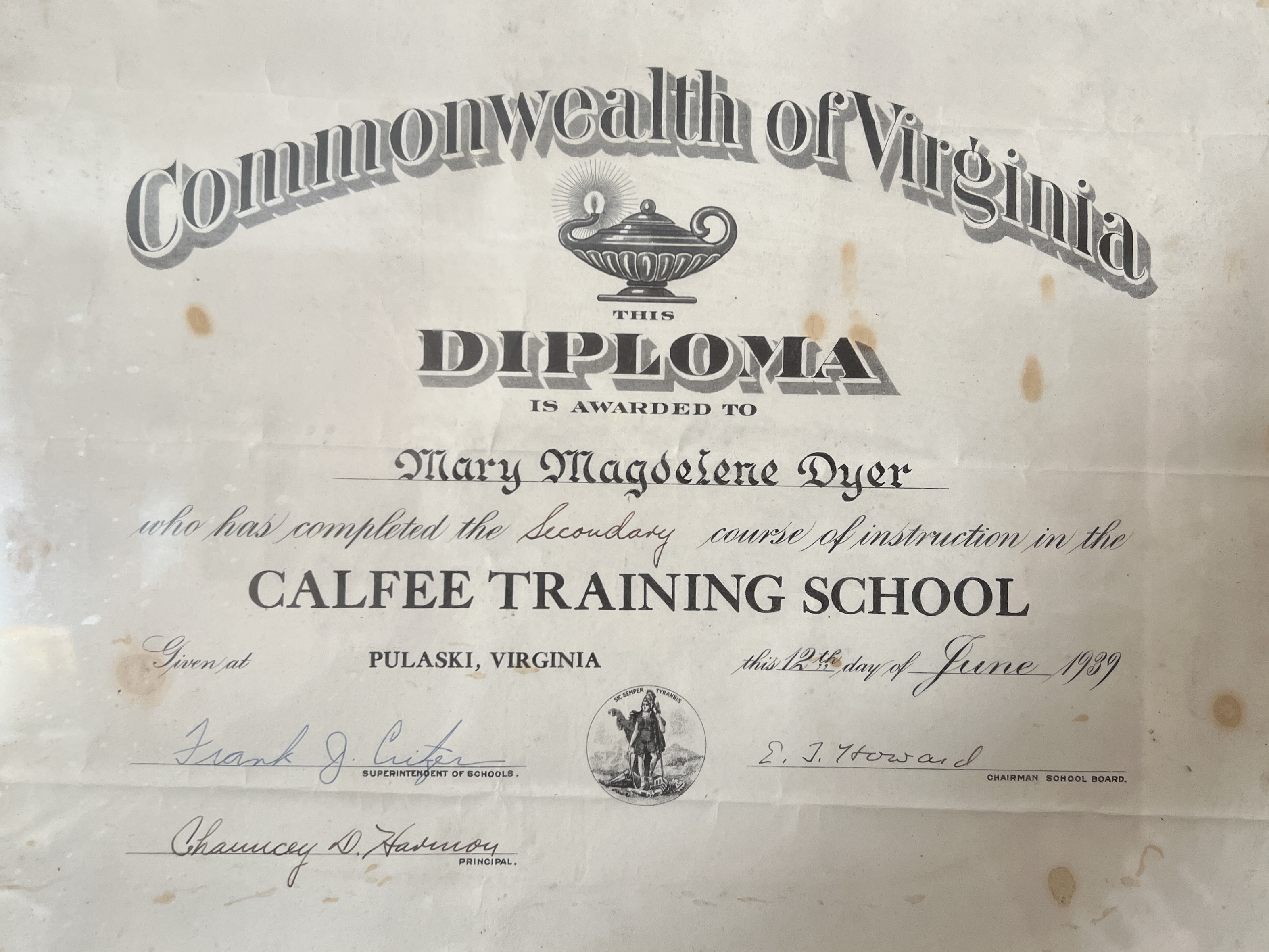

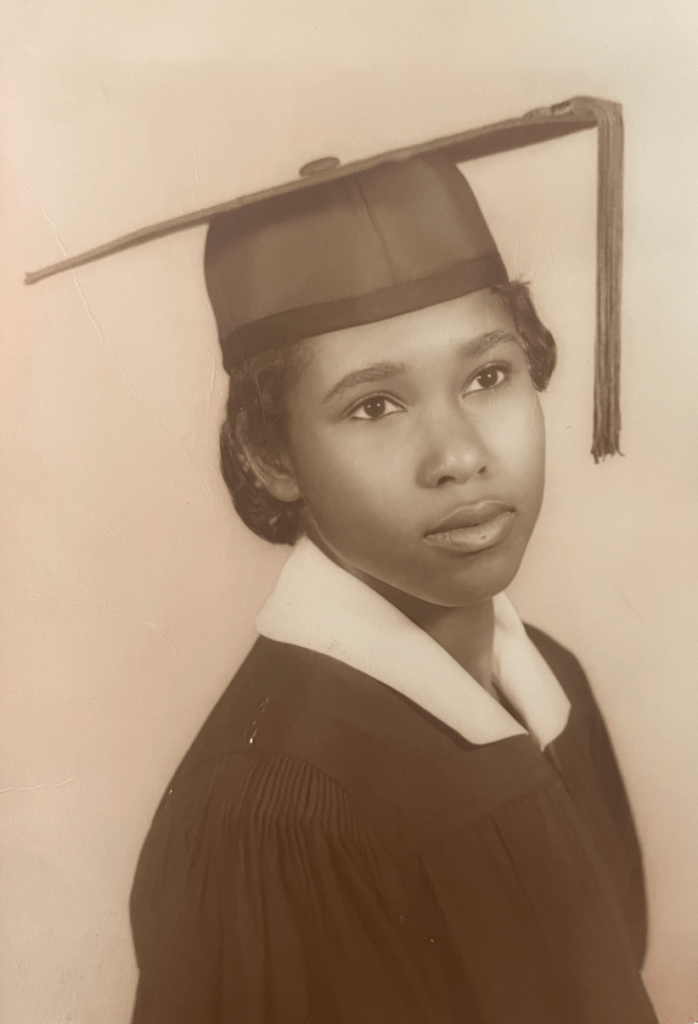

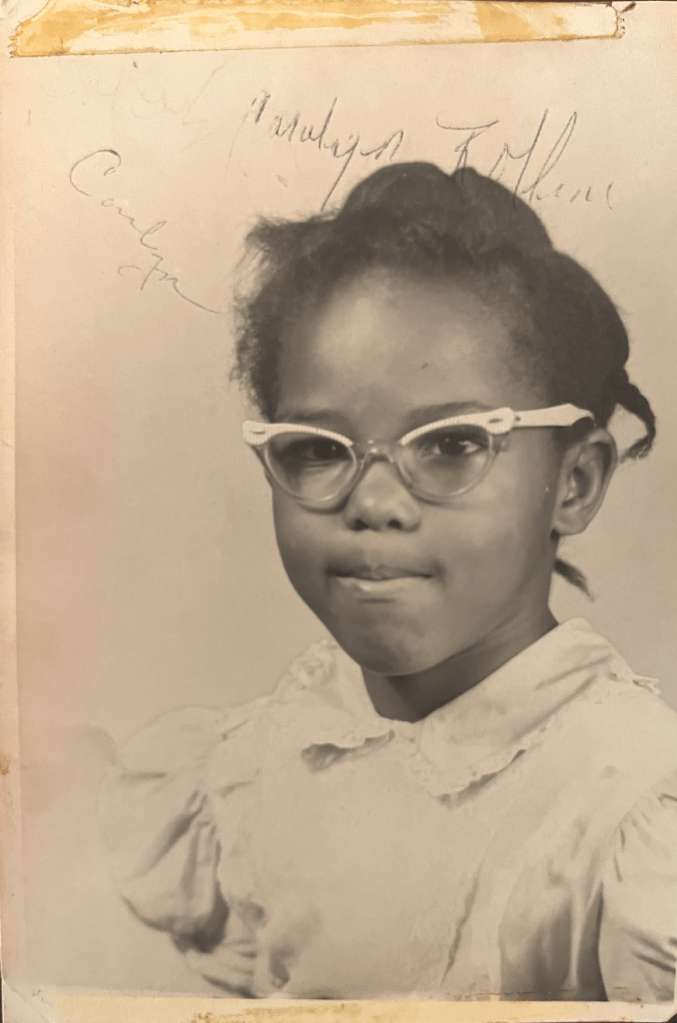

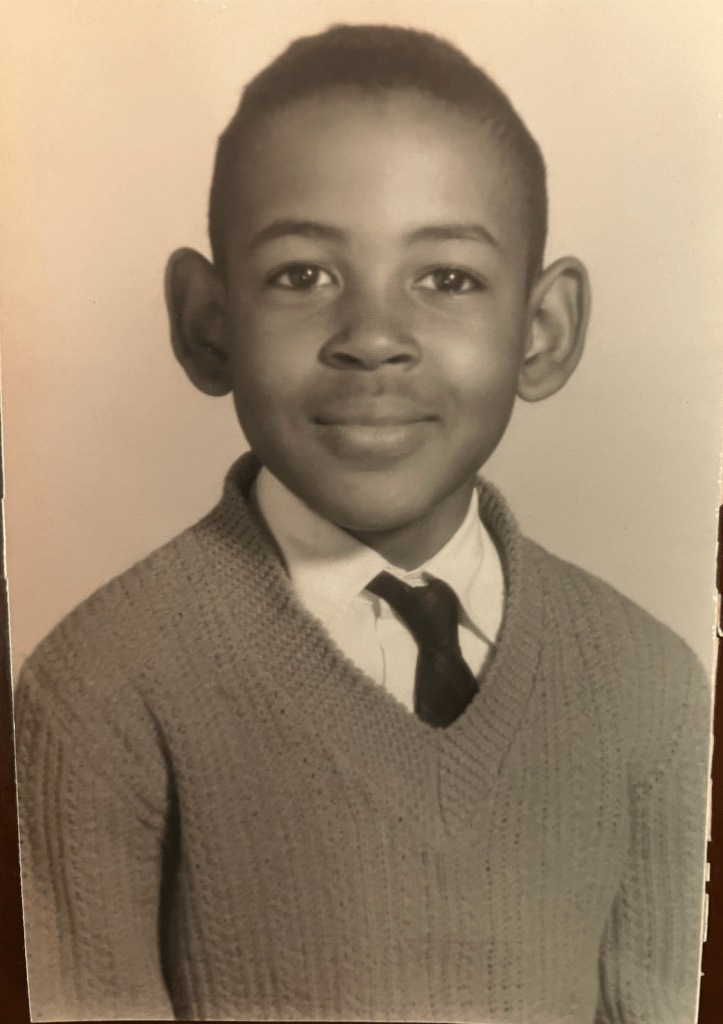

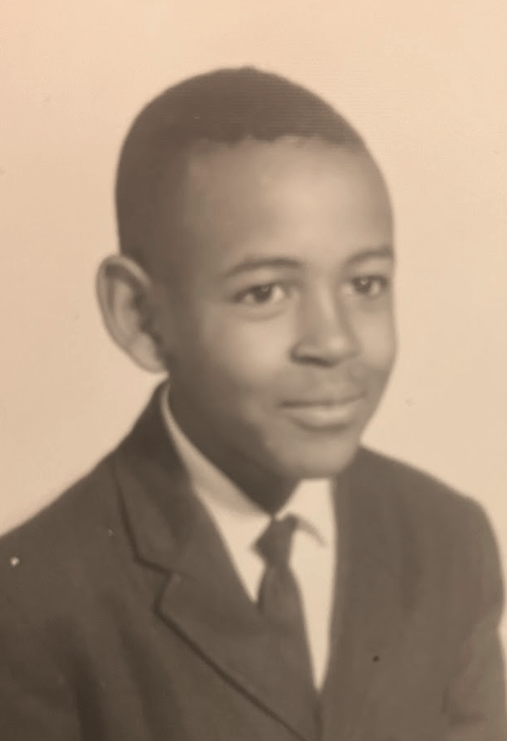

Mary Dyer Rollins

Summary

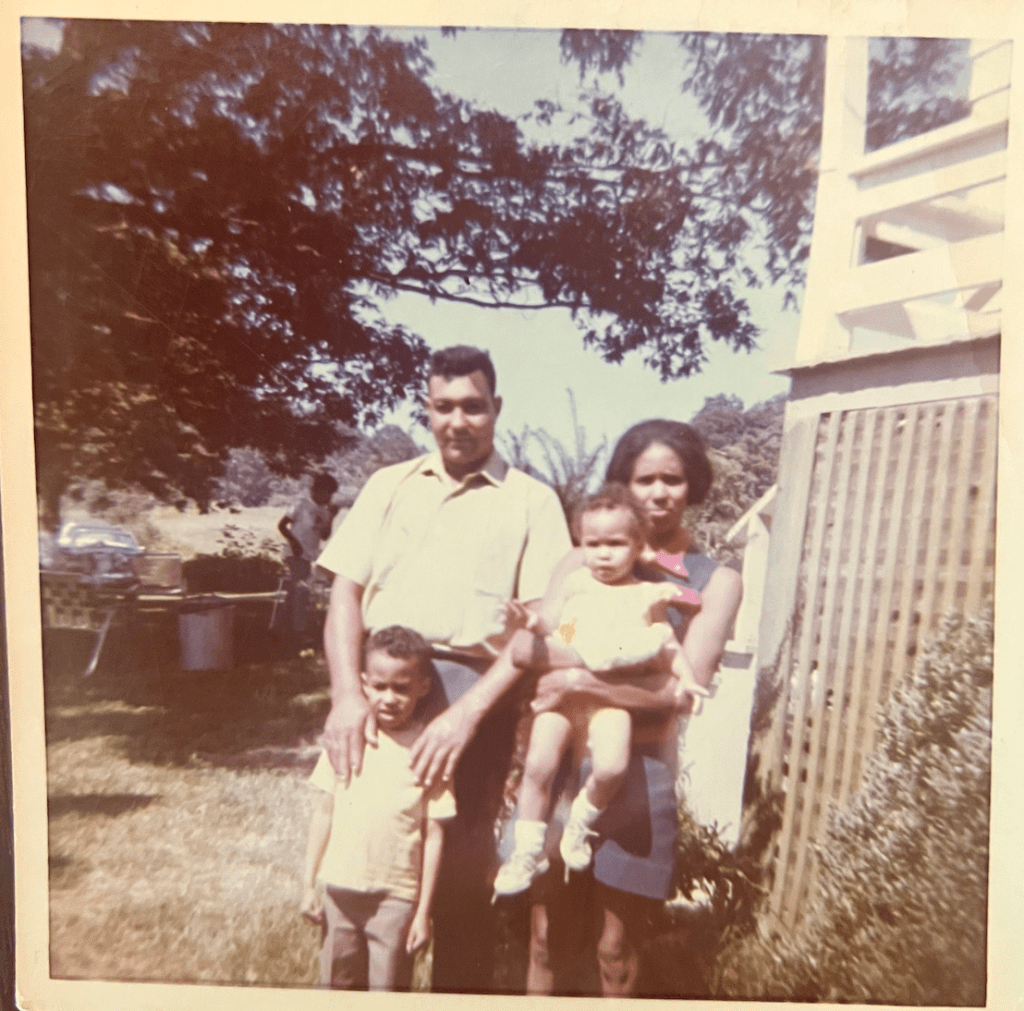

Mary Dyer Rollins was born on February 13, 1920, in Pulaski, Virginia, to parents John Henry Dyer and Malinda Austin Dyer. Mary had eight siblings: five brothers, Fountain, Henry Moses, John, and James; and three sisters, Pearl, Annie, and Ocie.5 Mary and her siblings grew up on Robinson Tract Road on her family’s plentiful farm. Mary then married Stanley Theodore Rollins, and the couple had five children: three daughters, Cynthia Gladden, Maggie Nicols, and Mary Carolyn Jones, and two sons, Stanley Rollins Jr. and John Rollins.6

Click on photos to enlarge them and to view captions.

Mary Rollins actively participated in her community as a member of Clark’s Chapel, which eventually merged with Randolph Avenue United Methodist Church. There, she served as the superintendent of the Bible School and a Vacation Bible School instructor.7 8 The Southwest Times highlighted Mary’s leadership in 1984 for World Community Day, a day for local churches to “see and hear the reality of human suffering” to put forth action to bring about justice and peace for all, regardless of circumstance.9 Mary’s compassion lived through her children, namely Cynthia Gladden, who the Southwest Times recognized in 1995 for her ten-year involvement in the SHARE (Self Help And Resource Exchange), a coalition of churches that served Southwest Virginians who needed food assistance.

10

Symbolic Representation

Calfee Diploma

Bus Seat

According to the family, Malinda Dyer had her own Rosa Parks-esque story in Pulaski, where she refused to give up her seat. “Pulaski used to have a bus service. Granny sat in the front of the bus, like Rosa Parks. They wanted her to move, but she wouldn’t.” African American women played a pivotal role in resisting segregation on public transport. These women relied on the bus system, and the bus system depended on their patronage. Actions by women like Claudette Colvin and Rosa Parks sparked a thirteen-month boycott of the Montgomery, Alabama, bus system. This boycott strained the bus system and put pressure on desegregation policies in the US. Small acts of defiance by women like Malinda demonstrate the power of everyday courage in igniting transformative change. 11

School Bus

Mary Dyer Rollins drove buses for Pulaski County Public Schools for over two decades, becoming a beloved and respected figure in the community. Her route covered the “Brook Martin-Robinson Track section of the county.”12 In 1976, the county honored her for safe driving. Her role was more than just a job; it was a responsibility that she upheld, making her a trusted presence in the community.13

“Few Misbehave on School Bus of ‘Dragon Lady’”

Despite her small stature, Mary Rollins’ commanding presence earned her the affectionate nickname of “Dragon Lady.” Mary ensured that her passengers behaved on her bus, saying, in a newspaper interview, that “you’ve just got to be firm.” This discipline extended to her children and grandchildren, who rode on her bus to school and were held to the same high standards as every other passenger. “My grandchildren think I’m rough on them,” she explained. If they misbehaved, they might be tasked with washing the school bus. Beyond enforcing the bus rules, Mary cared deeply for the students she transported. She took pride in safely getting her students to and from school every day.14

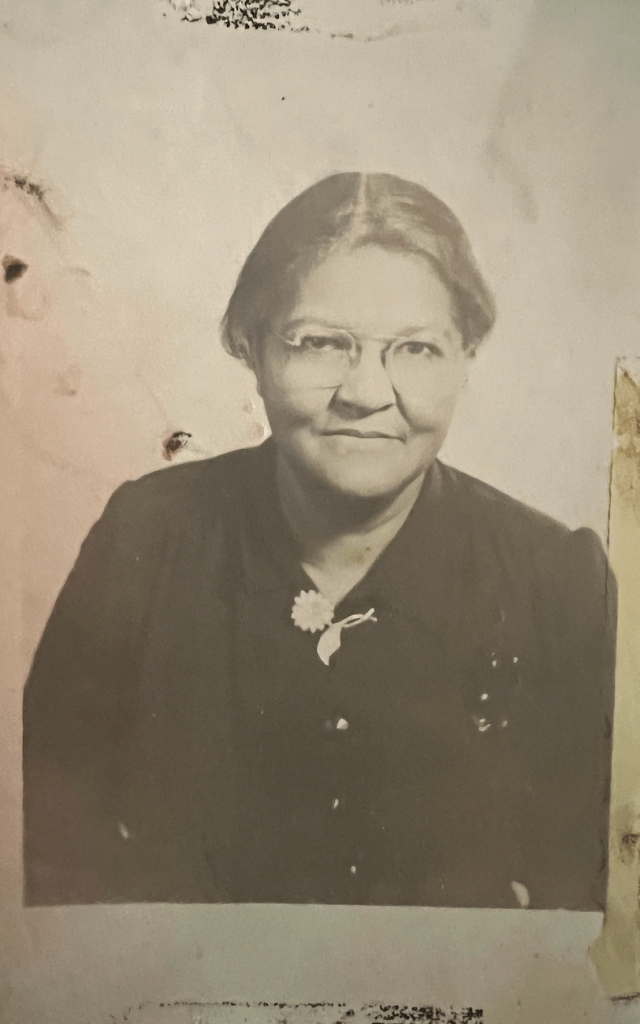

Malinda Dyer

Summary

Malinda Austin Dyer was born in 1890 to parents James Austin and Mary Steger in Pulaski. In 1914, she married John Henry Dyer and the couple started a family together on the family’s farm on Robinson Tract Road.

Symbolic Representation

Antique Stove

Malinda Dyer, the mother and heart of the family, was known for her love of cooking. Her granddaughters, Maggie and Cynthia, fondly remember her aptitude for cooking. Her old-fashioned stove, likely from the 1920s or 1930s, stood out most. They remember her rich desserts like coconut cake and extra-large cookies. Malinda is remembered for spreading her love through cooking for her children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

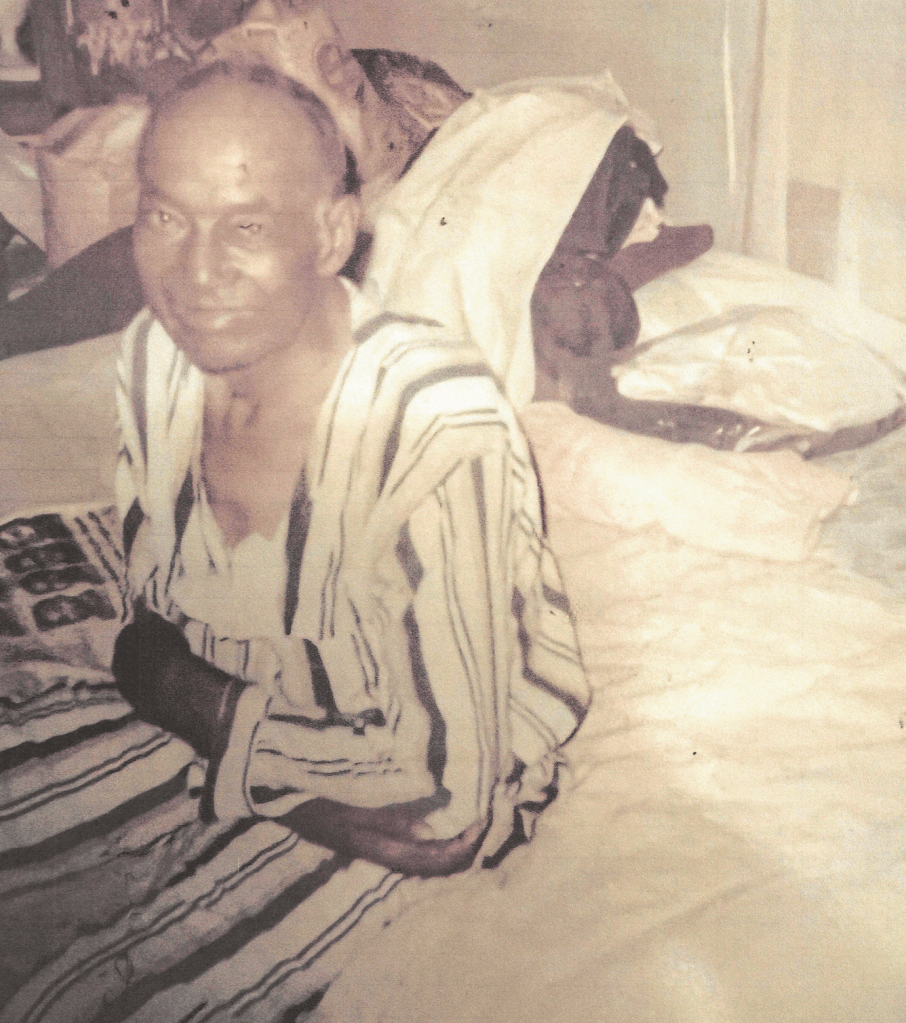

John Henry Dyer

Summary

John Henry Dyer Sr. was born in April of 1890 to parents John and Annie Phillips Dyer.15 John married Malinda Austin in the early 1900s and the couple had nine children Annie, Fountain, Pearl, Mary, Henry, Ocie, Moses, John, and James. For most of his life John worked incredibly hard as a farmer and a dairyman.

Symbolic Representation

Knife

According to his granddaughters, Cynthia and Maggie, John Henry had one peculiar habit at the dinner table. Their grandfather liked to carefully balance each one of his peas on the edge of a knife and enjoy them that way rather than with a fork or spoon.

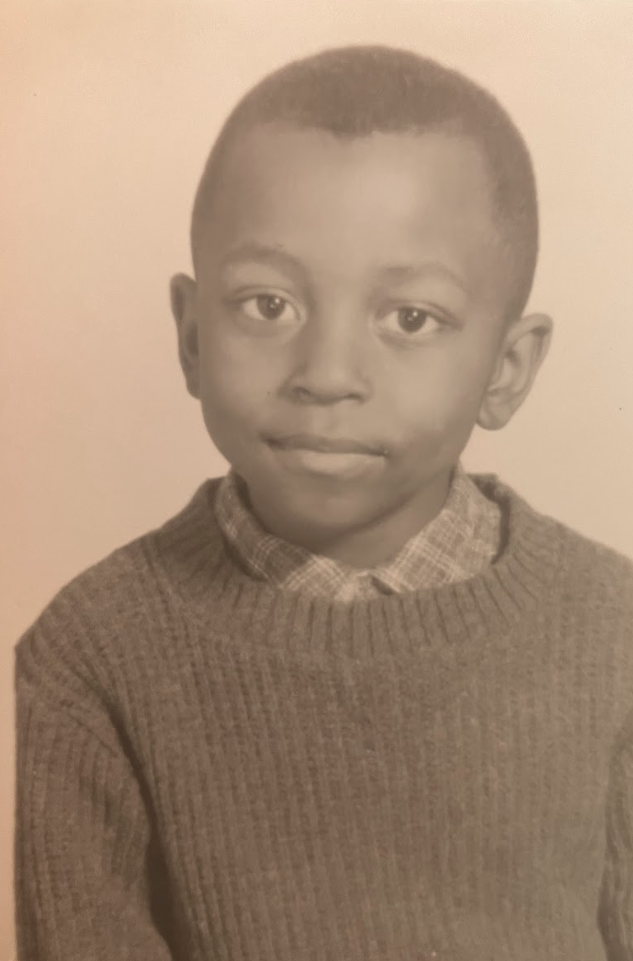

Amos Lee Andrew Hogans Jr.

Summary

Ocie Dyer married Amos Hogans Sr., son of Jethro and Lora Roberts Hogans, on December 8, 1953.16 Amos Lee Andrew Hogans Jr. was born in 1954 to parents Ocie and Amos Lee Andrew Hogans Sr. Amos Jr. was one of six brothers, Leon and Oscar Russell, Jethro “Billy” Hogans, Phyllis Jerome Hogans, and James Hogans. In 1962, Ocie and Amos Sr. passed away in a car accident which resulted in Mary Dyer Rollins, the boys’ Aunt, taking on the responsibility of caring for the boys.17 18 Amos Jr. eventually relocated to Florida with his brothers where they joined the military and found work.

Click on photos to enlarge them and to view captions.

Symbolic Representation

STS-1 Launch

According to his relatives, while living and working in Clearwater, Florida, Amos was involved in the shuttle project, in some capacity, for NASA’s 1981 STS-1 Launch. This was the first space shuttle, which took astronauts John W. Young and Robert L. Crippen on a successful mission orbiting Earth. 19

Other Artifacts

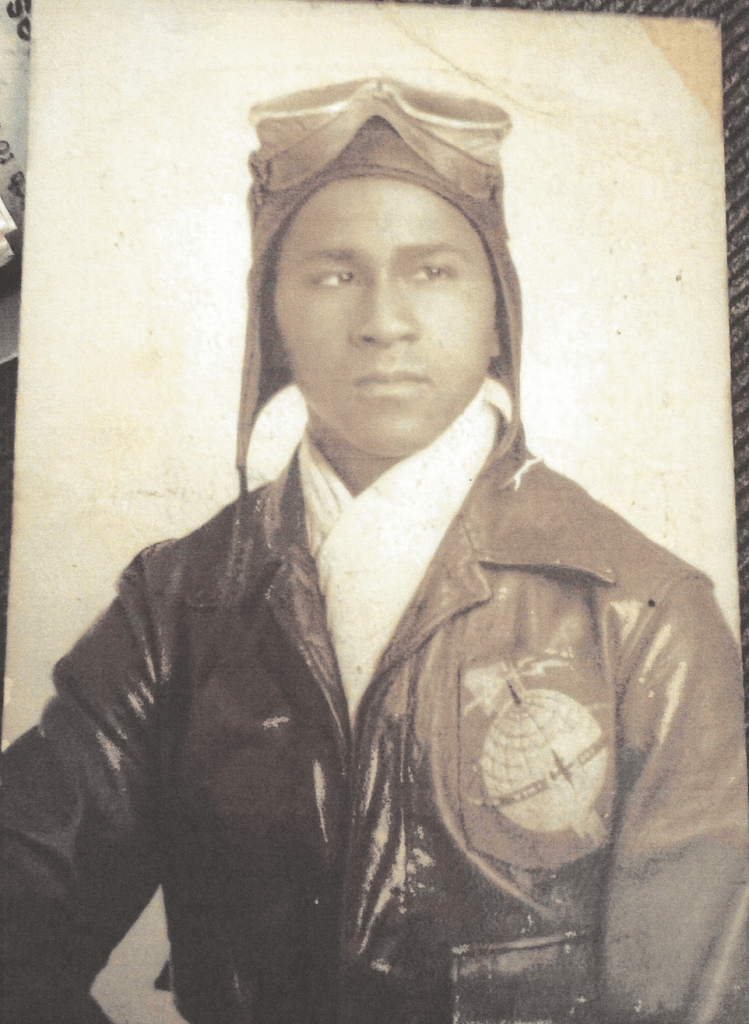

Soldier Saluting

The Dyer family demonstrated deep involvement in military service, exemplifying a collective dedication to their country. This includes, but is not limited to, Moses, Fountain, and Maggie serving in the Army, and Henry Lee and Jethro serving in the Marines. Their service spans many years and stretches across various locations, such as Texas, Alabama, and Iwo Jima. According to family representatives, many saw the armed forces as their only path out of Pulaski. This statement reflects a broader truth that “the armed services have been an important engine of opportunity for African American men.”20 Today, Black men and women make a marked contribution to the military and civilian service.21

“Welcome to the Dyer Family Farm”

The Dyer family lived an abundant life on the family farm on Robinson Tract Road. This farm was plentiful with livestock and plant life. The family raised chickens, dairy cows, and hogs. The family tended an extensive garden and fruit trees that grew produce for the family. Family farming traditions emerged on this land, like slaughtering hogs and canning. Most importantly, this land catalyzed cherished family memories like riding hogs and enjoying Malinda Dyer’s delightful home cooking. Part of the land from the original farm still remains in the family’s possession.

Girl Riding Pig

Cynthia Gladden and Magdalene “Maggie” Nicols were involved in all aspects of life on the family farm. As young girls, the pair would “ride hogs” around the farm for fun. The sisters took piggyback riding to a whole new level, holding tight onto their hogs as they shuffled through the open field.

Sources

- Commonwealth of Virginia Certificate of Death for John Schaffer Dyer. March 14, 1949. File number 6846. Pulaski, Virginia. Accessed on Ancestry.com. ↩︎

- “CII Student Burns Alive After Wreck.” The Southwest Times. March 13, 1949. Page 1. Accessed on Virginia Chronicle Library of Virginia Digital Newspaper Archive. ↩︎

- Christiansburg Institute Digital Archive. “John S. Dyer Award, 1951. Smokehouse Collection. https://hub.catalogit.app/8896/folder/entry/33212a00-1f45-11ee-8dcb-592174299212. ↩︎

- Corbin et al. v. County School Board of Pulaski County, VA. et al. 84 F. Supp. 253 (W.D. Va. 1949) May 2, 1949. ↩︎

- Mary Dyer Rollins Obituary. The Roanoke Times. May 12, 2012. ↩︎

- Commonwealth of Virginia Certificate of Marriage for Stanley Rollins and Mary Dyer. February 22, 1940. File number 6809. Pulaski, Virginia. Accessed on Ancestry.com. ↩︎

- Carter, Ethel. “Colored News Personal Mention.” The Southwest Times. July 3, 1949. Accessed on Virginia Chronicle Library of Virginia Digital Newspaper Archive. ↩︎

- Carter, Ethel. “Colored News Churches.” The Southwest Times. July 27, 1947. Accessed on Virginia Chronicle Library of Virginia Digital Newspaper Archive. ↩︎

- “World Community Day service planned in Pulaski, Thursday.” The Southwest Times. October 31, 1984. Page A8. Accessed on Virginia Chronicle Library of Virginia Digital Newspaper Archive. ↩︎

- Quesenberry, Wayne. “Gladden dedicated to her family, church, community.” The Southwest Times. February 26, 1995. Page B2. Accessed on Virginia Chronicle Library of Virginia Digital Newspaper Archive. ↩︎

- Norwood, Arlisha. “Montgomery Bus Boycott.” National Women’s History Museum. Accessed April 15, 2025. https://www.womenshistory.org/resources/general/montgomery-bus-boycott. ↩︎

- Weatherington, B.K.. “Few Misbehave on the bus of ‘Dragon Lady.’” Courtesy of the Dyer Family. ↩︎

- “Pulaski County Honors Drivers.” The Southwest Times. May 28, 1976. Page 6. Accessed on Virginia Chronicle Library of Virginia Digital Newspaper Archive. ↩︎

- Weatherington, B.K.. “Few Misbehave on the bus of ‘Dragon Lady.’” ↩︎

- Virginia Birth Register of Carroll County 1890. “John Henry Dyer.” Form 103. 47. Accessed on Ancestry.com. ↩︎

- Commonwealth of Virginia Certificate of Marriage for Amos Leander Hogans and Ocie Malinda Dyer. December 8, 1953. File number 37841. Pulaski, Virginia. Accessed on Ancestry.com. ↩︎

- “State Police Seek Answer To Wreck; Man, Wife Killed.” The Southwest Times. October 29, 1962. Page 1 and 2. Accessed on Virginia Chronicle Library of Virginia Digital Newspaper Archive. ↩︎

- Mary Dyer Rollins Obituary. The Roanoke Times. ↩︎

- “STS-1.” NASA. Accessed April 15, 2025. https://www.nasa.gov/mission/sts-1/. ↩︎

- Wilcox, Brad, Wendy Wang, and Ronald Mincy. 2018. “Black Men Making It in America: The Engines of Economic Success for Black Men in America.” American Enterprise Institute, (June), 1-32. ↩︎

- Reeves, Richard and Nzau, Sarah. 2020. “Black Americans are much more likely to serve the nation, in military and civilian roles | Brookings.” Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/black-americans-are-much-more-likely-to-serve-the-nation-in-military-and-civilian-roles/. ↩︎