Muse

Raymond Muse signed his children — Henry, Frances, James, and Sonja — as infants onto the Corbin et al. v. County School Board of Pulaski County (1947) lawsuit, joining other Black families in the fight for equal education. Born in Roanoke in 1906, Raymond worked as a laborer in a car garage at a time when African-American employment in auto trades was rare. Henry went on to serve as Senior Deacon of the Rose of Sharon Lodge No. 4 and became a mason; Sonja rose as a pianist in the National Fraternity of Students affiliated with the American Federation of Musicians; Frances trained as a nurse and was active in community service at her church in Roanoke; and James won a local boxing competition. The Muse family’s legacy is one of talent, dedication, and unwavering family bonds that carried them forward even as they reached new roles beyond their home community.

Explore the quilt by clicking on the various elements

For best user experience, use full screen mode

An interactive graphic of the quilt square. The linked information can also be found below.

The central theme of this quilt square is the Muses family’s deep sense of family and togetherness. The items displayed on the quilt vividly represent their close-knit bond and the profound connections among family members. The image on the quilt represents a house with a heart inside, symbolizing the love within the Muses’ family. This design reinforces the strong theme of family and togetherness that is rooted in the Muses’ family history.

Learn More About the Muse Family

Symbolic Representation of Theme

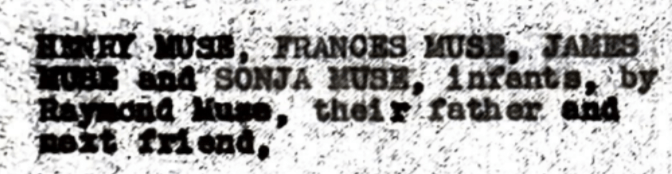

Family Names on Lawsuit

spacer

Father Raymond Muse signed on four of his children Henry Muse, the Eldest son, Sonja Muse, the Eldest daughter, Frances Muse, the Youngest daughter, James Muse, the Youngest son, onto the Corbin et al. v. County School Board of Pulaski County, VA. et al. court case filed in 1947.

spacer

Family, Service, Talent, and Dedication

These words were thought to best represent the family’s ideals and values. The research showed that the family had a tight bond. In addition, many articles about the family mentioned that they were dedicated and talented in their respective crafts and talents.

Artifacts by Family Member

Raymond Muse

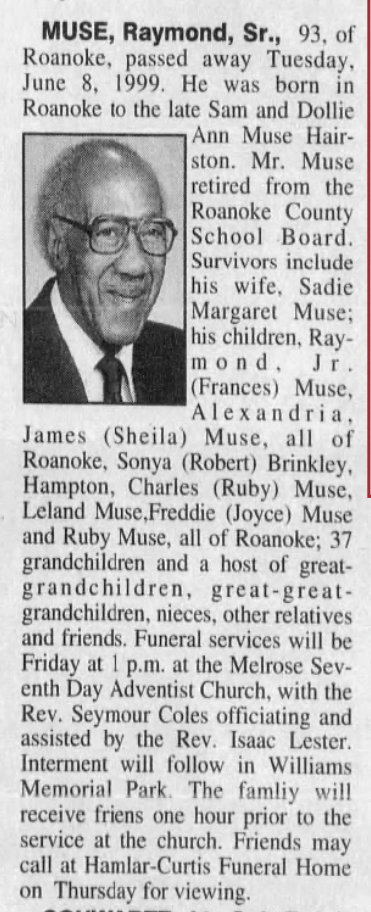

Photo of Raymond Muse

Picture of Raymond Muse, who signed on to the Corbin et al. v. County School Board of Pulaski County, VA et al. (1947)—Father of the Muse family. Raymond Muse was born in Roanoke, Virginia, in 1906 to Sam and Dollie Ann Muse. Before he retired, he worked for the Roanoke County School Board. He was also employed as a laborer in a car garage. He passed away on June 8th, 1999.1

Car

In the 1940s, Raymond Muse worked as a laborer in a car garage. At that time, African Americans comprised only about 3% of the auto industry workforce. Historically, the auto industry was discriminatory against Black laborers, often favoring white workers for higher-paying and more stable positions. Only the most qualified Black laborers were typically selected to work in the industry during this period.2

Henry Muse

Baseball

Like most Americans in the late 1940s, the Muse family had a strong fondness for baseball. During this time, Black America was captivated by players like Jackie Robinson3. and Larry Doby,4 who broke the color barrier and cemented baseball’s significance in African American history. The sport was so important that a father-son dispute over a game escalated into a physical altercation. Henry Muse threatened to “break up a ball game” between the Draper and Dublin teams. His father, Raymond Muse, was the manager of the Dublin team. The Raymond Muse, who managed the Draper team, according to witnesses, struck his son with a baseball bat after Henry threatened him with a knife. The altercation left Henry Muse unconscious and hospitalized. While Henry eventually regained consciousness, it can be assumed that he learned that day not to challenge his father over the game of baseball5.

Red Rose of Sharon’s Penchant

Henry Muse was a local mason at the Rose of Sharon Masonic Lodge, Lodge No. 4. He was titled a senior deacon. The African American Masonic tradition began in 1784 with a Black man named Prince Hall6. Black masons both practiced the sacred rituals of all freemasons but, in addition, used their organization to provide mutual aid to their communities and fight for social justice.7

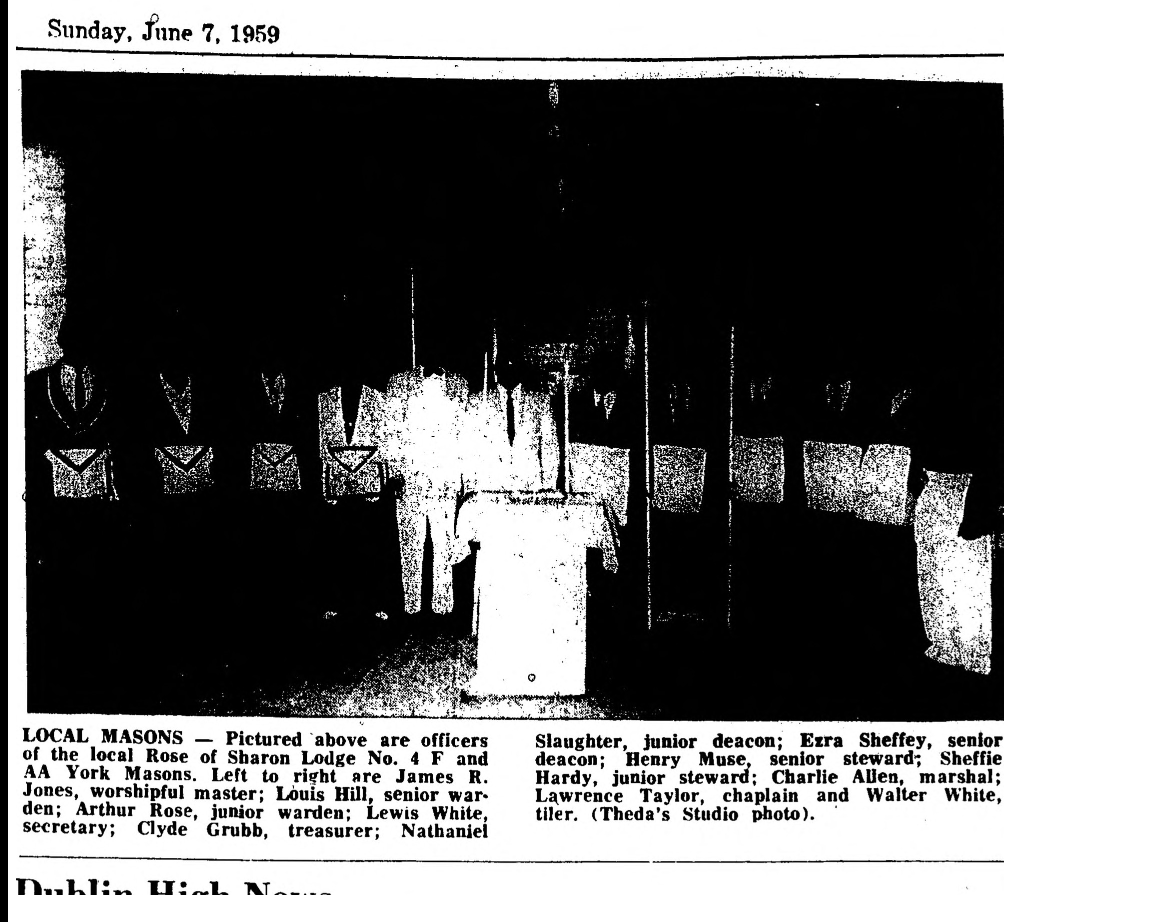

“Local Masons” Article clipping

Henry Muse, Nathaniel Slaughter, and Clyde Grubb were photographed as officers of the local Rose of Sharon Lodge No. 4. Henry Muse was listed as the Senior Deacon of this Sharon Lodge. The African American Masonic tradition began in 1784 with a Black man named Prince Hall.8 Black masons both practiced the sacred rituals of all freemasons but, in addition, used their organization to provide mutual aid to their communities and fight for social justice.

Sonya Muse

Sonja Muse, daughter of Raymond, was a pianist granted local status in the National Fraternity of Students (Carter 1950), an organization affiliated with the American Federation of Musicians (AFM).9 Like many fraternities and institutions of its time, the American Federation of Musicians (AFM) was segregated. The first AFM charter for Black musicians was established in Chicago in 1902. A “separate but equal” status was the norm within the institution. However, in 1941, when the AFM granted autonomy to all local chapters, Black locals gained the right to elect their own representatives and send delegates to the national AFM convention.10

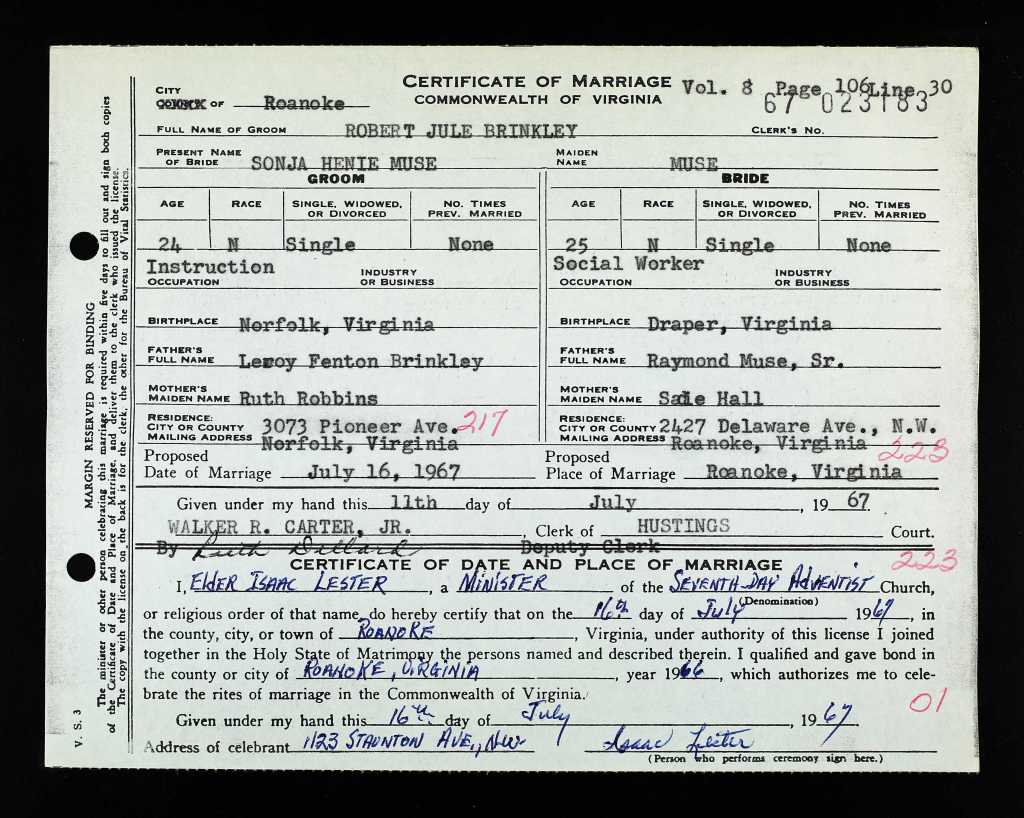

Sonja Henie Muse and Robert Brinkley Marriage Certificate

Frances Muse

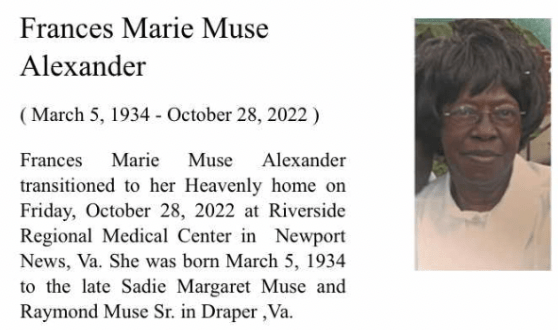

Frances Muse was born March 5, 1934, in Draper, Virginia. She graduated from Lucy Addison School in Roanoke, Virginia, and then attended a vocational college to obtain her nursing license. Frances’s muse worked for multiple nursing homes in the Roanoke, Virginia, area. Frances was also a member of the Melrose Seventh-day Adventist Church of Roanoke, Virginia, where she served as a community service worker, a deaconess, and an usher.

The Caduceus

After attending vocational school, Frances Muse received her Nursing Assistant license and practiced in Roanoke, Virginia. Roanoke had a history of segregation in its health field, leaving the African American community with inadequate healthcare.11 In the 1950s, Black nurses had few options when it came to becoming a licensed health professional, and many times nursing students found themselves struggling under the structural oppression that occurred during the 1950s in the healthcare field.12

“Here comes Aunt Frances, and she doesn’t play”

Frances’s obituary mentions a quote in which her children and grandchildren reflected on her strict no-play attitude.

Sewing Machine

In her obituary, Frances was noted to enjoy arts and crafts, specifically sewing. Frances Muse’s fondness for arts and crafts reflects a long history of African American sewing and quilting traditions. During slavery, Black women often created quilts both as a form of expression and out of necessity, adding to their sparse bedding and sleeping materials13. In the 20th century, sewing for African American women evolved from a means of survival to an avenue for artistic expression. Many Black women learned to sew at home, making dresses and other pieces of clothing. In addition, sewing was a communal activity, with church sewing circles commonly found in Black communities.

Sign of a Deacon

Frances Muse was a Deacon at the Melrose S.D.A. Church of Roanoke. While historically, most church leadership roles were reserved for men, women in the Deaconry date back to the early beginnings of the Christian church. The same is true in the Seventh-day Adventist denomination of Christianity. The late 19th-century Adventist Movement had women actively involved in ministry and preaching the gospel. Frances Muse’s role as A Deacon reflects a long tradition of women in church authority.14

James Muse

Calfee Graduation article Clipping

In 1950, about 58 percent of elementary school graduates received diplomas from secondary school. In comparison, only about 10% of African Americans in 1950 went on from primary school to graduate from high school. Schools that served Black students were significantly underfunded compared to white schools. Calfee was no exception. James Muse’s graduation from Calfee and his attendance at Addison High during his boxing years show his perseverance and dedication to his education.

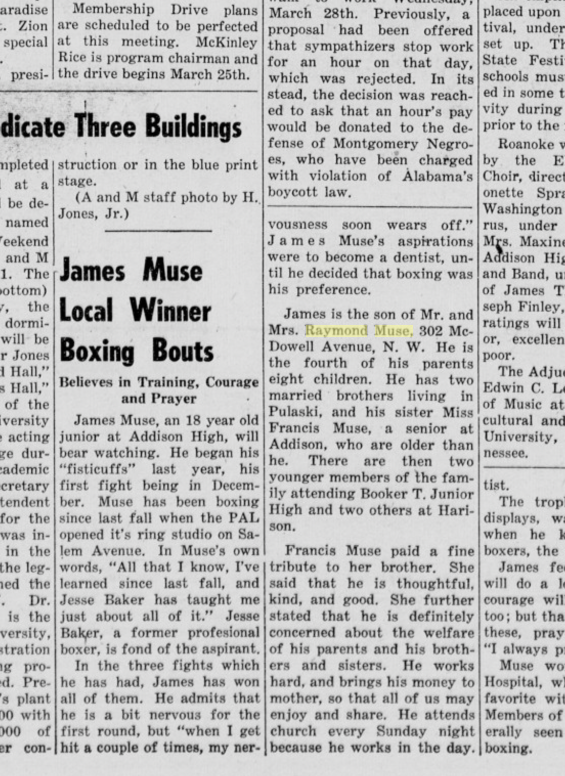

James Muse Local Winner Boxing Bouts

This is a clipping from an article celebrating James Muse’s boxing win. The article also mentions Francis Muse and compliments her brother, saying he was hardworking and talented. 15

In the 1950s, boxing was often segregated, and weight classes were sometimes divided along racial lines.16 However, boxing directly challenged the image of a subjugated Black man that was common in America’s mind. With the first Black boxers breaking records and rising to fame due to their successes, a picture was painted of a strong Black America, breaking the color lines that pervaded American sports.17 A 1959 U.S. Supreme Court decision titled United States v. The International Boxing Club finally granted boxing18.

In 1956, James was honored for his boxing win with a feature in the Tribune newspaper titled “James Muse: Local Winner Boxing Bouts.” At 18, as a student at Addison High School, he had been boxing for about a year before his celebrated win. Jesse Baker, a former professional boxer in the area, mentored him. James was undefeated at the time of the article, winning three out of all three fights he’s ever had. Initially aspiring to become a dentist, his boxing successes led him to pursue a career in the sport.

- “Raymond Muse Obituary”, The Roanoke Times, June 10, 1999. Accessed on Ancestry.com ↩︎

- Sugrue, Thomas J. Driving While Black: The Car and Race Relations in Modern America. University of Michigan–Dearborn: Autolife. http://www.autolife.umd.umich.edu/Race/R_Casestudy/R_Casestudy5.htm#popsugrue. ↩︎

- “The Road to Baseball Integration.” Philadelphia Phillies, MLB Advanced Media, LP. https://www.mlb.com/phillies/community/educational-programs/uya-negro-league/road-to-baseball-integration. ↩︎

- National Baseball Hall of Fame. “The History of Baseball and Civil Rights in America.” Baseball Hall of Fame. https://baseballhall.org/civilrights ↩︎

- “Negro Lad Fails to Rally after Blow Upon Head.” The Southwest Times, June 14, 1948. ↩︎

- “A Brief History of Prince Hall Freemasonry.” Scottish Rite, Northern Masonic Jurisdiction. Accessed July 28, 2025. https://scottishritenmj.org/blog/prince-hall-freemasonry. ↩︎

- “Prince Hall Masons.” Searchable Museum. https://www.searchablemuseum.com/prince-hall-masons/. ↩︎

- “Prince Hall Masons.” Searchable Museum. https://www.searchablemuseum.com/prince-hall-masons/. ↩︎

- “American College of Musicians – National Guild of Piano Teachers (512) 478-5775.” 2025. Acmglobal.org. 2025. https://acmglobal.org/ ↩︎

- “American Federation of Musicians.” 2023. Rochester, 2023. https://iml.esm.rochester.edu/polyphonic-archive/resource/american-federation-of-musicians/index.html

↩︎ - “Healing Horizons: A Legacy of Health in Roanoke.” 2015. https://medicine.vtc.vt.edu/inclusivevtc/health-history.html ↩︎

- “Race and Place in Virginia.” University of Virginia School of Nursing, 2021. https://nursing.virginia.edu/news/bhm-claytor/ ↩︎

- “Through the Folk Art of Quilting, Tracy Vaughn-Manley Works to Preserve Black American History and Culture.” Weinberg College News https://news.weinberg.northwestern.edu/2023/02/14/tracy-vaughn-manly-works-to-preserve-quilting-history-at-northwestern/ ↩︎

- “History of Women Deacons.” 2011. http://catholicwomendeacons.org/explore/explore-historydetails ↩︎

- “James Muse Local Winner Boxing Bouts.” The Roanoke Tribune, March 10, 1956. ↩︎

- “Black Boxers and Golden Gloves, from Segregation to National Champions,” Notable Kentucky African Americans Database, 2021. https://nkaa.uky.edu/nkaa/items/show/300004299 ↩︎

- “Boxing the Color Line.” American Experience: PBS. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/fight-Black-boxers-and-idea-great-white-hope/ ↩︎

- “International Boxing Club v. United States, 358 U.S. 242 (1959).” Justia Law. 2025. https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/358/242/ ↩︎